By David Underhill –

MOBILE, Ala. – Remember those photos from Pakistan several years ago? Squadrons of unruly lawyers in suits and ties, some with flowing wigs left over from British imperial days, wielding brief cases like cudgels in the streets to protest an insult to themselves and the constitution by autocratic rulers? Now picture a mob of rowdy artists and primly attired leaders of arts orgs marching on Government Plaza in Mobile to demand an end of budget cuts for their activities.

Won’t happen. That was apparent from the demeanor of the gathering last week at the downtown quarters of the Mobile Arts Council. They jammed into a gallery filled with chairs for the occasion and overflowed into the hall. The size of the turnout and their grave manner reflected their anxiety. But there was no open anger, no seething or incendiary denunciations of flinty accountants and artless philistines in the city government. The meeting was very mild, very modulated, very Mobile.

Mayor Sandy Stimpson assembled this crowd by presenting to the city council the first proposed budget of his new administration. It whittled or chopped the funding for numerous groups that had grown to expect some boost from the city, along with other sources of money.

These included the Boys and Girls Club, which offers an alternative to life on the streets, especially in the housing projects. Also Family Promise, which among other activities co-ordinates churches volunteering meals and temporary housing for families without such essentials. Leaders of these and other organizations have issued plaintive pleas for restoration of their funding but have not yet summoned their clients for public protest.

The Arts Council did that. It convened “a meeting of Mobile’s Creative Community to develop a united pan of action regarding the future of public funding for the nonprofit organizations that provide vital opportunities and services.â€

This was not an invitation to the homeless, hungry or sick who rely on services by groups with shrinking city funding. It was meant for painters, sculptors, potters, musicians, divas, ballerinas, actors—and for the staffs of orgs that shepherd the arts.

The latter packed the meeting, properly dressed and mannered citizens who would not look misplaced at any respectable civic event. Absent were actual artists living their art. No paint-flecked clothes and hair. No clay-grimed hands and nails. No preening performers. No avant unkempt bohemian radical fizzy or frazzled aesthetes.

Or if any such were present, they had cleaned themselves up for the occasion and were striving to maintain decorum. For a while.

Bob Burnett, executive director of the Arts Council, presided. He outlined the impending cuts and suggested responses. Then he invited questions and comments from the audience.

They mostly flowed along with his ideas: Seek more funding from private donors, businesses and foundations. Write and call the mayor and city council members urging restoration of the arts money. Remind them that the arts make the city more vibrant, attractive and liveable. Remind them that the arts, rather than a frill or a drain, are an investment that stimulates the economy.

Some speakers were dismayed that the mayor, after campaigning as a friend of the arts, would assault them in his first budget. A few said that no amount of reason and persuasion would succeed, that only raw political clout could win.

We Interrupt This Message

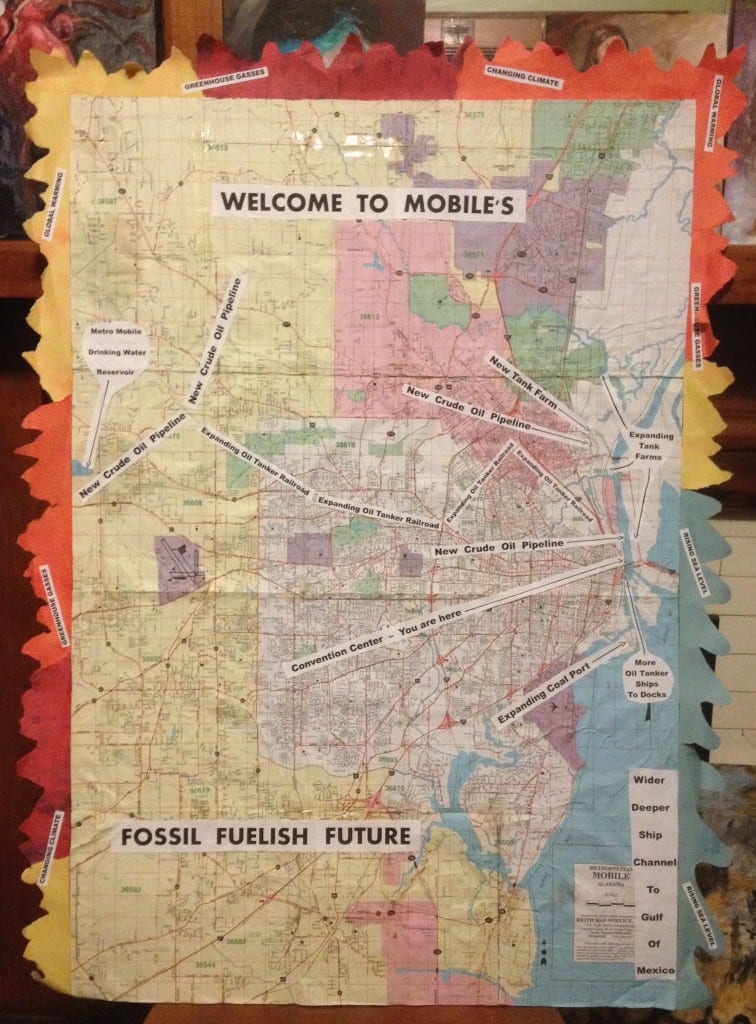

Then Burnett called on somebody (the author of this article) with a large annotated city map pasted to a poster board. Art, he called it. His additions showed the recent invasion of Mobile by crude oil pipelines, railroad tanker cars, expanding waterfront tank farms and coal terminals. A flaming border depicted global warming and climate change, a blue wavy stretch was rising sea levels.

This speaker noted a pattern that others had also mentioned—without drawing any conclusions from it. Most of the proposed cuts affected downtown orgs and activities. But some things in the westerly suburban sprawl sectors were getting increases, a big tennis complex and the municipal golf course, for instance.

The pattern reveals, he said, the intentions of those maneuvering to turn the downtown waterfront into a major fossil fuel handling hub. Houston East, he called it. To further this plan they want to discourage revival of downtown into a lively, appealing place to live and enjoy. Allowing developments like that would create a flock of folks resistant to surrendering the city center to oil, coal and the highrise white collarites servicing these industries. That’s why the mayor’s budget takes aim at the downtown arts orgs.

But he didn’t get to say this all at once because he was interrupted. By Carol Hunter of the Downtown Mobile Alliance, which is friendly to the arts but even friendlier to businesses. Also by the Arts Council’s Burnett, who questioned the relevance of these matters to the issue at hand. Actual artist Walter Simon, painter and musician, intruded from the hallway to interrupt Burnett and defend the beleaguered map adapter.

That ended this odd interlude, except for a couple lingering references, and the meeting reverted to the approach Burnett had suggested. The groups represented agreed to assess the economic impact of their functions and to present this to the politicians, along with a pitch about their orgs’ contributions to the city’s quality of life. Individuals pledged to do the same.

This was very standard stuff, an aggrieved interest group organizing to insert itself into a budget tussle. And it has had some standard results. The mayor soon retreated a bit from a few parts of his scheme. But the main features remain and the outcome is uncertain.

Many Divided One

Meanwhile, some lessons are already apparent.

First, mayor Stimpson is who he is. He campaigned for the office last year as somebody else, the champion of One Mobile, running against an incumbent black mayor in a city roughly half black, half white with astounding extremes of luxury and poverty separated into neighborhoods displaying these splits. It was soothing to believe he could magically unify the divides, and many in the arts community did so.

But before Stimpson was Mr. One Mobile he was chairman of the local chamber of commerce and its statewide equivalent. These clubs are hardly emblems of oneness. They are designed to gather the reins of the economy into the guiding hands of their exclusive members.

He was also chairman of the Alabama Policy Institute. It describes itself as a “conservative think tank…dedicated to the preservation of free markets, limited government and strong families,†which means: Keep the damn government out of my affairs, don’t dare tax me for anything I dislike, and let me do whatever I please with my private property.

And before that he passed his entire life in the shelter of inherited wealth and privilege, not oneness.

His initial budget withholding government funds from downtown arts activities and services for the poor faithfully reflects who he is. Anybody surprised at this should be kept away from itinerant peddlers of investment opportunities and from online Nigerian princes with fortunes awaiting.

Crony Core

Second, your core functions are my cronyism. The mayor proclaims in his budget and elsewhere that he intends to fashion Mobile into “the safest, most business and family-friendly city in America†by focusing municipal administration on “core functions.â€

These include the police, who are blessed by the budget, public works like parks, streets, drainage, and “economic development.â€

Preachers and politicians are routinely pleased to discover that God’s desires and prejudices neatly match their own. Economic development is similar. If an offshore oil well explodes, that’s a calamity for fishing communities and coastal ecology. But to emergency response and restoration contractors it’s economic development.

Mayor Stimpson has said being business friendly means easing rules and supervision by government. In reply to citizens’ questions about the wisdom of enlarging coal docks and oil storage tanks on the waterfront, he replaced the planning commission members most receptive to these concerns with appointees more receptive to him. Facilitating the arrival of toxic and explosive mega-cargoes in the heart of the city becomes a core function of government. And that accords with previous gifts of millions in tax breaks to the expanding tank farms.

This isn’t economic development. It’s a choice to favor one type of activity — and the cronies who engage in it — over other types that could also stimulate the economy but are not chosen. The difference is that activities motivated by the lust for money are deemed worthy pursuits that government should use its powers to promote. Activities like the arts that merely aim to make life worth living are options that should rely on private resources or die—especially if those activities are downtown where they might conflict with the expansion of fossil fuel operations around the waterfront.

Creative Community Cripples Creative Community

Third, the arts haven’t a prayer of deflecting the budget cuts if their defenders persist in calling themselves the “creative community,†as they casually do. To win—or simply to survive — in the contest with the forces arrayed against them, they need allies.

Picture the pitch:

“Hi, I’m from the creative community and we should work together. We can help each other.â€

“Creative community? Is that like the Creator? You think you’re God?â€

“Uh, no. We’re creative in the things we do. Music, painting, stuff like that.â€

“You think it don’t take creativity to get by on a minimum wage job, or none? To get your car fixed or prescriptions filled when you can’t afford it? To get around when you don’t even got wheels?â€

“Uh……â€

A chasm between the arts community and people outside that enclave was evident in the paintings on the walls of the gallery during the meeting. Notice in the first photo the elegant butterflies and luxuriant peacocks and lounging ladies. This echoes the art of the late 19th – early 20th century’s Gilded Age, when the phrase “conspicuous consumption†became the apt description of ostentation amid deprivation.

The works of Aubrey Beardsley in England and Gustav Klimt across the Channel snared the spirit of the era. It ended in 1914 with the Great War, followed by the Great Crash. From that came socialist realism in revolutionary Russia—and the tamed version of it in the US produced by artists on the federal payroll during the Depression.

Examples of this endure in murals at the entrance to Mobile’s old city hall, now a history museum. The peacocks and the ornamented idle are gone.

In their place are the sorts of folks the Arts Council would need as allies to save themselves from the budget guillotine. To foster this artists could descend from their creative community pedestal and make art addressed to the throngs below, instead of pandering to the conspicuous consumption of a new Gilded Age.

Then the moment might come when they could emulate the lawyers of Pakistan. In league with their new allies they march on the city council’s budget hearing at Government Plaza.

It would be an artsy thing to do—a latter day re-enactment of this French revolutionary painting. And it would be patriotic.

This picture became the model for the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor. What could be more patriotic than that?

The author of this article is right. It’s pretty obvious Mr. Stimpson’s capital improvement budget means to fix the city up to be business friendly–and we’d better get real about the types of businesses the improved infrastructure is aiming to facilitate. It’s as plain as the nose on your face.