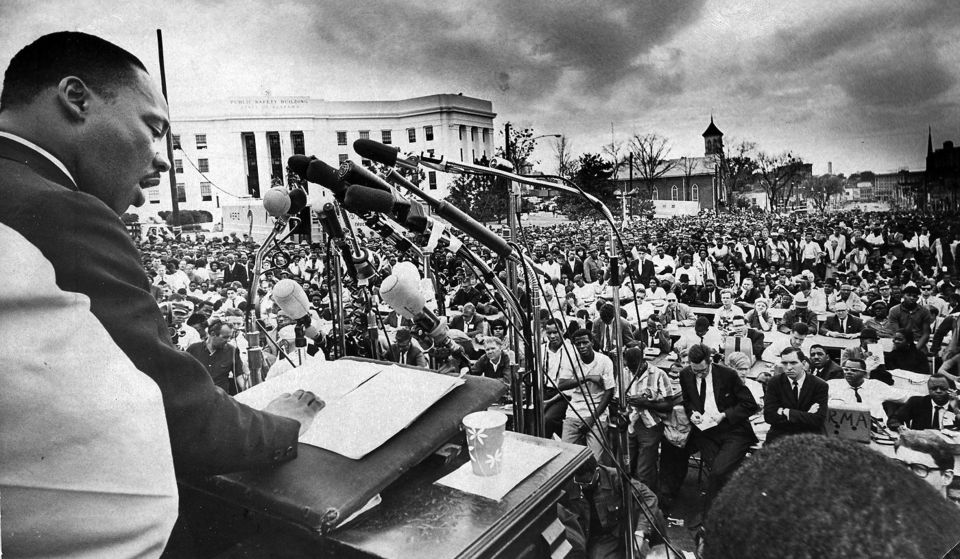

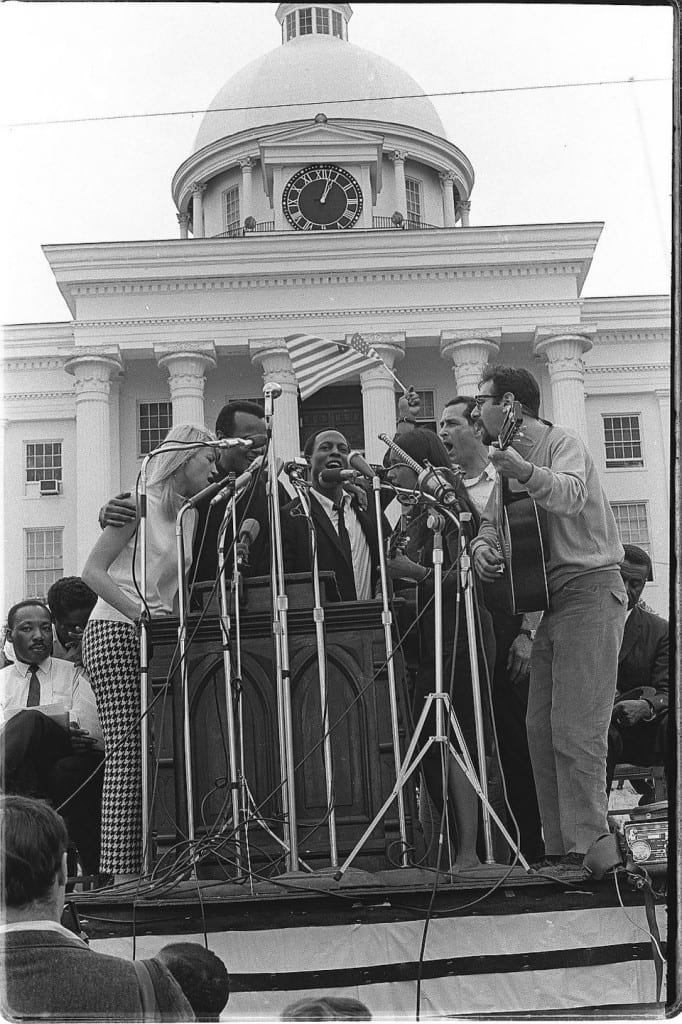

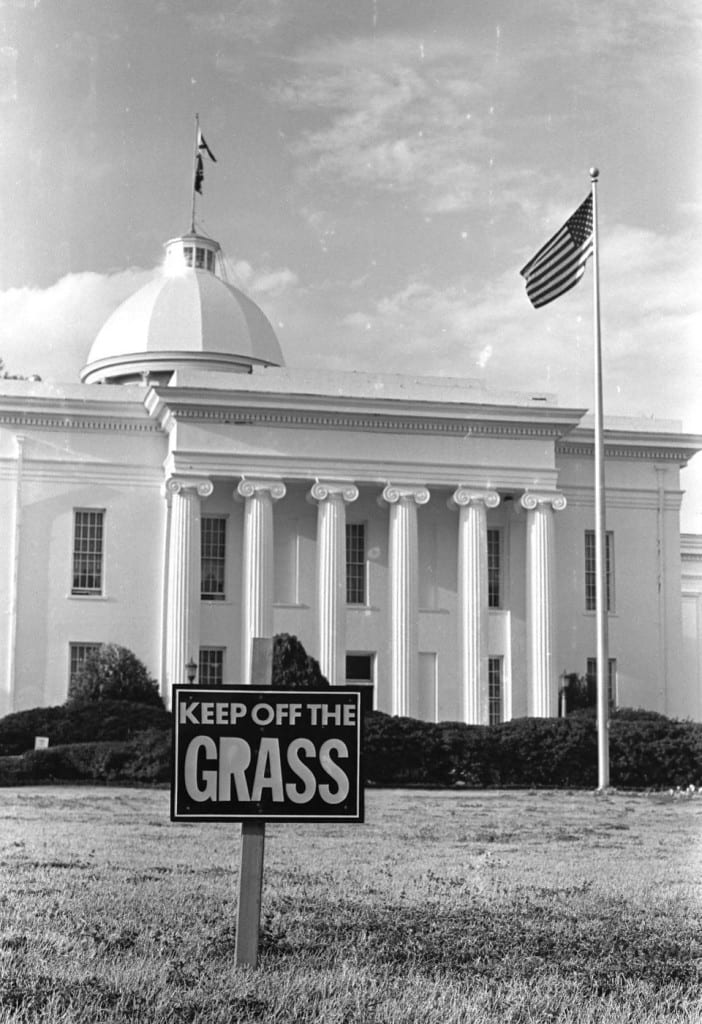

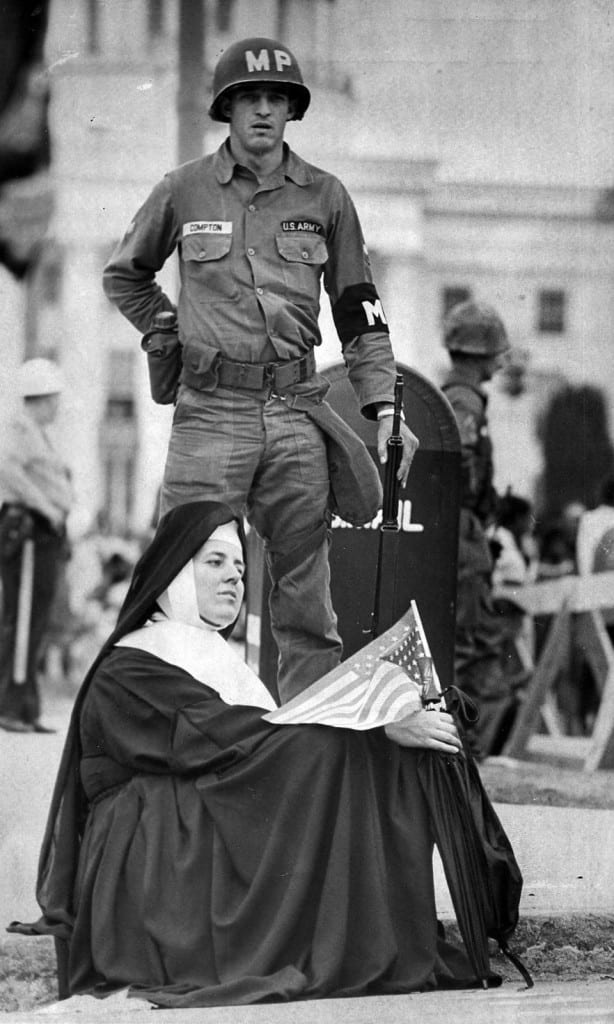

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. addressing hundreds of protesters on the Alabama Capitol steps in Montgomery at the end of the final and successful Selma to Montgomery march in 1965: James Spider Martin

By Glynn Wilson –

MOBILE, Ala. — If you are really any kind of patriotic American — Republican or Democrat, conservative or liberal, libertarian, whatever — you must be willing to acknowledge that what happened in Alabama and Washington in 1965 was a pivotal moment in U.S. and world history.

By “pivotal” I do not just mean important or big or even seminal. It was of crucial importance to the future success of the uniquely American experiment in pioneering a democratic republic “of the people.” It was the third major chapter of the American Revolution, the Civil War being chapter two. Of course there are still living factions in this country — especially in my native South — who would like to go back in time to before what they call “The War Between the States” or “the War of Northern Aggression.”

The buzz from the right on Facebook and Twitter is predictable: It’s “liberal propaganda.”

Right. Then say with a straight face on Facebook that you are NOT a “racist?” Come on. Not even your mama is buying it. Look deep into your heart if you are really interested in the truth or the future of American democracy.

I caught the film in a Daphne, Alabama theater on the Gulf Coast by Mobile Bay after catching an interview about the controversies with former New York Times editor Howell Raines at his southern home in Fairhope. Every other ticket buyer on a Saturday was asking for “American Sniper,” many of them obviously there because the buzz in conservative circles is out: Clint Eastwood’s film can be interpreted sympathetically to the cold blooded killer, while the real story that will go over many heads is the personal and national tragedy of it all.

“Selma: One Dream Can Change the World,” on the other hand, was sparsely attended here — even though this to me seems to be a better patriotic choice than Sniper — and the small audience was mostly silent throughout the production. This for me was one indication of why the film was “snubbed” at the Oscars, if you pay attention to the sensational story line on broadcast television or cable talk.

Maybe, while it is a well made film — and should be with a budget of $22 million — and tells a fine and important story over all, is it possible that in the end there is not a masterful performance to justify a golden Oscar?

Even Bill Moyers, who criticized the film for its portrayal of Lyndon Johnson as an obstructionist to non-violent protests to push for voting rights, says it is a powerful and poignant story well worth seeing. Howell Raines agrees, as I do after seeing the film.

But even before I read Moyer’s remarks — who was there and knows way more about what actually went down than I, even though I’m a journalist from Alabama steeped in the story — I did not find it overwhelmingly commanding. As a long-time best friend of photographer Spider Martin, whose powerful and artistic pictures grace most online and print newspaper coverage of the film and obviously influenced some key scenes in the movie as well, I have heard the stories and seen the photos and footage before. Spider even makes something of a cameo appearance in the film, even if it is as an extra portraying him running around in a trench coat and hat photographing the Selma to Montgomery marches.

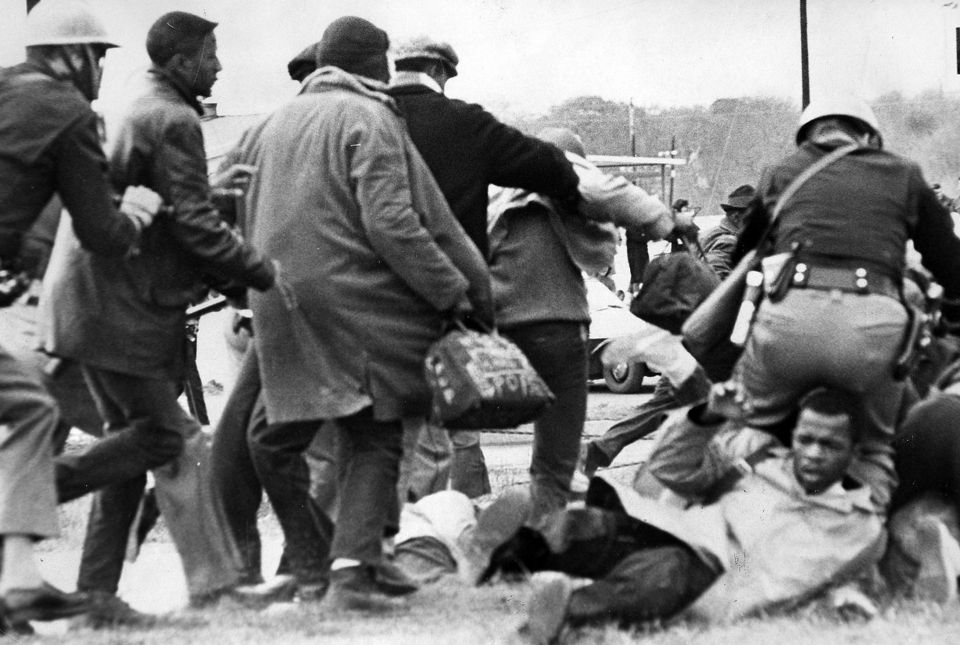

There were a couple of opportunities lost here, and Moyers highlights the biggest one. The movie climaxes when the marchers made it to Montgomery in the final successful march — after the televised violence on Bloody Sunday had galvanized the nation and forced President Johnson’s hand to put forward the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

It is understandable that making it to Montgomery unscathed would be a powerful moment for those involved up close in the story. But let’s face facts. The marches were a means to an end. The end was not making it to Wallace’s Montgomery. It was passage of The Voting Rights Act in Washington, D.C.

“This is the moment when the film blows the possibility for true drama — of history happening right before our eyes,” Moyers says.

“To my knowledge he (Johnson) never suggested Selma as the venue for a march. But he’s on record as urging King to do something to arouse the sleeping white conscience. And when violence met the marchers on that bridge, he knew the moment had come,” Moyers says. “He told me to alert the speechwriters to get ready and within days he made his own famous ‘We Shall Overcome’ address that transformed the political environment.”

“Here the film is very disappointing,” Moyers says. “The director has a limpid president speaking in the Senate chamber to a normal number of senators as if it were a ‘ho hum’ event. In fact, he made that speech where State of the Union addresses are delivered – in a packed House of Representatives. I was standing very near him, off to his right, and he was more emotionally and bodily into that speech than I had seen him in months. The nation was electrified. Watching on television, Martin Luther King Jr. wept.”

Now that would have made for a climax scene worth remembering. The film stars David Oyelowo as King, who is incredibly believable even though his accent as a Brit comes through a time or two. But if there is a commanding performance in the film, it is delivered by another Brit, Tom Wilkinson, who portrays President Lyndon Johnson. His scenes with Alabama Governor George Wallace do appear to be right on the money.

Howell Raines Interview

“I came down pretty much where Bill Moyers did,” Howell Raines said in an in-person interview (video above), even though he gives the film a lot of credit for being a good telling of the Selma story.

“He (Moyers) thought it was a distorted representation of the King-Johnson relationship. As a journalist and historian who had a lot of experience in that era, that’s pretty much where I came down,” Raines said.

Raines, who reported for the Birmingham Post-Herald not long after graduating from Birmingham Southern in 1964, did not get to make the trek to Selma to cover the marches. But he did cover the death watch in Birmingham of the Unitarian minister James Reeb from Boston, Massachusetts, who was beaten up by white supremacists in Selma while there to participate in the march. He died of head injuries two days later after being taken to UAB hospital by ambulance.

The film inaccurately portrays Reeb dying on the street in Selma, Raines said. “But that kind of dramatic license is perfectly acceptable.”

“I’m more dubious about what they do with Johnson,” he said. “I hope I’m wrong about the motive, but in a way I felt like they put some of (John) Kennedy’s doubts and even offenses against King onto Johnson, perhaps to make Kennedy look better in comparison. Because the historical record is clear that Johnson was friendlier with King and more committed to getting the legislation through than Kennedy had been.”

Kennedy did draft the civil rights bill in 1963 that Johnson signed as president after Kennedy’s tragic death in Dallas that became the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“But his (Kennedy’s) relationship with King was very wary,” Raines says.

Bobby Kennedy went south to try to get King and Fred Shuttlesworth to call off the Birmingham demonstrations, and Raines says the Kennedy brothers were aware that FBI director J. Edger Hoover was spying on King. Even Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the First Lady, has said her husband told her before the big “I have a dream” march on Washington that there were wiretaps of “King and women.”

“It’s ironic that Jack Kennedy would be rating out another philanderer,” Raines said with a wry smile.

As for the “tilt with Johnson,” he said. “It’s not an accurate depiction of the fullness of the relationship. Every relationship has conflict, and there’s no doubt Johnson would have been happier if there were not demonstrations. But his commitment to the cause and his understanding of King were both deeper than Kennedy’s.”

That said, he indicated he was as impressed as I was with Wilkinson’s portrayal of Johnson.

“You get the feeling that you are seeing the real Lyndon Johnson, including the looming physical presence,” Raines said.

In the center pole scene with George Wallace and Lyndon Johnson, Raines indicates, Wallace says he lacks the power to order voter registration because the county officials have charge of that.

“In the movie,” he said, “Johnson leans forward and says, ‘Don’t you shit me George Wallace.'”

In fact that did happen, Raines says, and one of the sources was his book My Soul is Rested. “There’s no question that line in the film, which is the most shocking in the movie, is absolutely accurate.”

As for the Hollywood controversy about the snub on Academy Award nominations, Raines said he didn’t know enough about the other movies to rate Selma alongside them.

“The film was a film that would rise to the category of being considered for Oscar nominations,” Raines said. He thought the performances by the actors who played King and Johnson “would be worthy of consideration.” But he indicated that “how they stack up against the other nominees I just don’t know.”

My own educated take is that if the film maker had simply demonstrated how the non-violent activism of the marches forced the president’s hand, instead of mis-portraying the president as an obstructionist, there could have potentially been an Academy award winning credit to go with this movie for its own place in the history of film.

Casting the president as opposed to the Selma march, which the film does, “is an exaggeration and misleading,” Moyers says. “He was concerned that coming less than a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, there was little political will in Congress to deal with voting rights. As he said to Martin Luther King Jr., ‘You’re an activist; I’m a politician,’ and politicians read the tide of events better than most of us read the hands on our watch. The president knew he needed public sentiment to gather momentum before he could introduce and quickly pass a voting rights bill. So he asked King to give him more time to bring Southern ‘moderates’ and the rest of the country over to the cause. But once King made the case that blacks had waited too long for too little, Johnson told him: ‘Then go out there and make it possible for me to do the right thing.’”

Other critics have pointed out the same thing. LBJ Presidential Library Director Mark Updegrove alleged the film portrayed President Lyndon Johnson as an “obstructionist.”

“When racial tension is so high, it does no good to suggest that the president of the U.S. himself stood in the way of progress a half-century ago,” he said. “It flies in the face of history.”

While acknowledging King and Johnson had disagreements, for example after Johnson stripped an important voting rights provision from the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Updegrove argued such disagreements were not as tense as the film suggests and that the two in fact had a close partnership. In an article for Politico, he said Johnson felt it was best to “break the back of Jim Crow” before pushing for voting rights legislation and cited a taped phone conservation between Johnson and King on January 15, 1965 which described the strategy the two had formulated to pressure Congress into passing the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Joseph A. Califano, Jr., who was Johnson’s top assistant for domestic affairs from 1965 to 1969, also wrote a piece in the Washington Post that highlighted historical inaccuracies in Johnson’s portrayal.

“In fact, Selma was LBJ’s idea,” Califano said. “He considered the Voting Rights Act his greatest legislative achievement. He viewed King as an essential partner in getting it enacted — and he didn’t use the FBI to disparage him.”

Film director Ava DuVernay responded to these criticisms in posts on her Twitter account, saying, the “Notion that Selma was LBJ’s idea is jaw dropping and offensive to SNCC, SCLC and black citizens who made it so.” In a subsequent post, she went on to link to a New Yorker magazine article, saying, “LBJ’s stall on voting in favor of War on Poverty isn’t fantasy made up for a film.”

On the January 4, 2015 edition of MSNBC’s Up with Steve Kornacki, former SCLC executive director and activist Andrew Young said that “President Johnson did not say ‘it had to wait.’ He said, ‘I have a great agenda.’ …

“We did not expect him to commit,” Young said. “We were really kind of letting him know that we had to pursue voting rights. His agenda, I found out later, was that he thought that the Great Society would be easier for him to bring first. If he had said that, we would probably have agreed with him. But we didn’t have a choice.”

Young also criticized the film’s suggestion that Johnson ordered the FBI surveillance and harassment of King.

“It was actually Robert Kennedy who signed the order allowing the FBI to wiretap all of us. We knew we were bugged, but that was before LBJ.”

On that point Moyers says: “There’s one egregious and outrageous portrayal that is the worst kind of creative license because it suggests the very opposite of the truth, in this case, that the president was behind J. Edgar Hoover’s sending the ‘sex tape’ to Coretta King. Some of our most scrupulous historians have denounced that one. And even if you want to think of Lyndon B. Johnson as vile enough to want to do that, he was way too smart to hand Hoover the means of blackmailing him.”

In a 2013 New Yorker article, Louis Menand has Johnson explaining to King “…that he was worried that Southern opposition to more civil-rights legislation would drain support from the War on Poverty…” and other programs, and concluded: “He asked King to wait.”

So there is some truth in that, but this film fails in other ways, apparently due to director Ava DuVernay’s inexperience and bias — not a badly researched script.

Responding to the criticism in Rolling Stone magazine, she said the original script was more focused on “the LBJ/King thing,” … “originally … much more slanted to Johnson,” she admits. But, “I wasn’t interested in making a white-savior movie; I was interested in making a movie centered on the people of Selma.”

But surely all Americans can agree about the blow to American democracy by both men’s assassinations by extremists. Of course the Facebook conservatives will disagree — but no serious politician who plans to serve a national constituency. Even George W. Bush and Alabama Governor Robert Bentley have indicated how important the Civil Rights movement was to us all.

I totally agree with Moyers that there are some beautiful and poignant moments in the film that take us closer to the truth than anything in other movies to date. And some of it is highly effective. In the lead in to the film, without giving it away totally, if you know your history you know the bomb blast is coming when the little black girls are walking down the 16th Street Baptist Church steps. But that does not prevent you from nearly jumping out of your seat when it comes. It definitely gets your attention.

Then as Moyers says, he came out of the theater shaking his head in disbelief at the obscenity of the Republican Party as it has piously but insidiously taken up voter suppression as a priority. I was thinking the same thing.

“The Party of Lincoln? Of Emancipation? Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” of 50 years ago has now become their subliminal mantra: “Whites of America, Unite,” Moyers says.

But he concluded: “So it’s a powerful but flawed film.”

Background

Selma premiered at the American Film Institute Festival on November 11, 2014, began a limited U.S. release on December 25. It expanded into wide theatrical release on January 9, 2015, just two months before the 50th anniversary of the march. Special ceremonies are planned this year for that anniversary, and we will be there to cover some of them.

Selma had four Golden Globe Award nominations, including Best Motion Picture–Drama, Best Director and Best Actor. It only won for Best Original Song. It was also nominated for Best Picture and Best Original Song at the 87th Academy Awards, but none of the lead characters were nominated for Best Actor awards, nor was the director nominated.

In July 2013, it was announced that Ava DuVernay had signed on to direct the film for Pathe UK and Plan B, and that she was revising the script with the original screenwriter, Paul Webb. Those revisions included rewriting King’s speeches, because, in 2009, King’s estate licensed them to DreamWorks Pictures and Warner Bros. for an untitled project to be produced by Steven Spielberg. Subsequent negotiations between those companies and Selma’s producers did not lead to an agreement, so DuVurnay is credited with writing alternative speeches that evoke the historic ones without violating the copyright. She apparently spent hours listening to King’s words while hiking the canyons of Los Angeles. While she did not think she would “get anywhere close to just the beauty and that nuance of his speech patterns,” she did identify some of King’s basic structure, such as a tendency to speak in triplets: saying one thing in three different ways.

In early 2014, Oprah Winfrey came on board as a producer along with Brad Pitt, and by February 25 Paramount Pictures was in final negotiations for the U.S. and Canadian distribution rights.

Selma has received universal acclaim from film critics. Praise has gone particularly to the film’s acting, cinematography and screenplay. On Rotten Tomatoes the film currently holds a rating of 99%, based on 144 reviews, with an average rating of 8.7/10. The site’s critical consensus reads, “Fueled by a gripping performance from David Oyelowo, Selma draws inspiration and dramatic power from the life and death of Martin Luther King, Jr. — but doesn’t ignore how far we remain from the ideals his work embodied.”

The Official Trailer

More Spider Martin Photographs

Our Previous Coverage

We covered the 47th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery March in great depth three years ago. You can see all our coverage here:

Selma-to-Montgomery March No Celebration of the Right to Vote This Year

Post Script

We were just having a conversation over here about all this, and it occurred to me I didn’t deal with it in the story about the movie. But it is part of Martin Luther King’s brilliance – and a lesson in making democracy work which I deal with in my upcoming book.

The film features the role New York Times and CBS News reporters played in the success of the Civil Rights movement by showing reporters asking questions, taking notes and calling in stories in phone booths. It also showed people, including the president and the governor, reading the front page of the newspapers and watching the coverage on television. At one point, one of the civil rights leaders say to the others, “70 million people are watching this.”

Martin Luther King said to Spider Martin that without the photographs and the coverage, the gains of the civil rights movement would not have been fulfilled.

He knew, and activists should understand today, that without “drama,” and thus news coverage, your movement is probably going nowhere.

That is an important lesson that is fairly explicit in the film.

Reader Supported News - No Paywall, Google Ads, Popup Ads, Sponsored Content or A.I. - Support American Journalism with GoFundMe

Looking forward to seeing the film. Enjoyed you on Radio or Not with Nicole Sandler.