The public can experience history with a tour on this 105 foot gaff-rigged schooner called the Alliance in the port of Yorktown, Virginia and ride out into Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean: Glynn Wilson

By Glynn Wilson –

YORKTOWN, Virg. — I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Of all the federal holidays in the United States, Independence Day, which falls every year on the Fourth of July, is my favorite in many ways. This year thanks to a trip to Yorktown, I am thanking the French.

If you drill down into the history of the event, however, there are some interesting things to learn about American History and arguments could be made that we should be celebrating on other dates.

I try to do something different every year to celebrate the holiday. In 2014, for example, my first year back in the Washington, D.C. area after a long hiatus taking care of my elderly mother in Birmingham, Alabama, I had the idea to photograph and video the Fourth of July fireworks on the National Mall from the Lady Bird Johnson Park on an island in the Potomac River near the Pentagon. The view of the fireworks and the Washington Monument across the river provide an iconic scene.

Independence Day Fireworks From Washington, D.C.

This year, when my good friend Brooks Boliek had the idea to do a day trip to Yorktown, Virginia, I was all in. I had never before visited the scene of the last major land battle of the Revolutionary War and the location of the long siege that broke the back of the British military and government will and desire to hold onto the American colonies as part of that nation’s vast global empire.

There are many other places in the country where one could plan a patriotic visit on this occasion, from historic sights in Boston, Philadelphia and elsewhere. But only about a three and a half hour drive from D.C., Yorktown is also a logical day trip.

Before we set out, with free day passes from a National Park Service ranger as reward for our volunteer service on National Public Lands day, the question came up:

Why do we shoot fireworks on the Fourth of July?

There are a couple of parts to the accurate historical answer for that. When Congress finally got around to establishing a national holiday for Independence Day in 1870, about 95 years after the American Revolution began with the first shots at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, in 1775, history had been recorded on the wishes of several of the so-called Founding Fathers.

First there was the letter from John Adams, a Federalist delegate to the Continental Congress from Massachusetts, to his wife Abigail dated July 3, 1776, the day most of the members of the delegation signed the Declaration of Independence. But the final wording was not adopted and approved by a vote of the Continental Congress until July 4.

Adams thought the Second Day of July 1776 would “be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America,” according to the letter. “I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

Then, in 1826, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both died on July 4 on the 50th anniversary of the ratification of the Declaration of Independence. So that’s why we celebrate on the Fourth of July.

But what were the key events that led to independence in the first place?

It gets really interesting with the story of what happened during the military campaigns that culminated in the Siege at Yorktown in the summer and fall of 1781.

While there are far more books and biographies that detail much about the American Revolution, the story of Yorktown is not so well covered or remembered. But one promising book by retired National Park Service historian Jerome A. Greene offers a detailed account: The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781.

A summary of this account can be found in the review at Amazon.com.

The siege of Yorktown in the fall of 1781 was the most decisive engagement of the American Revolution. The campaign has all the drama any historian or student could want: the war’s top generals and admirals pitted against one another; decisive naval engagements; cavalry fighting; siege warfare; night bayonet attacks; and more. Until now, however, no modern scholarly treatment of the campaign has ever been produced.

By the summer of 1781, America had been at war with England for six years. No one believed in 1775 that the colonists would put up such a long and credible struggle. France sided with the colonies in 1778, but it was the dispatch of 5,500 infantry under Rochambeau in the summer of 1780 that shifted the tide of war against the British.

In early 1781, after his victories in the Southern Colonies, Lord Cornwallis marched his army north into Virginia. He believed the Americans could be decisively defeated in Virginia and the war brought to an end. George Washington believed Cornwallis’s move was a strategic blunder, and he moved vigorously to exploit it. Feinting against General Clinton and the British stronghold of New York, Washington marched his army quickly south. With the assistance of Rochambeau’s infantry and a key French naval victory at the Battle of the Capes in September, Washington trapped Cornwallis on the tip of a narrow Virginia peninsula at a place called Yorktown. And so it began.

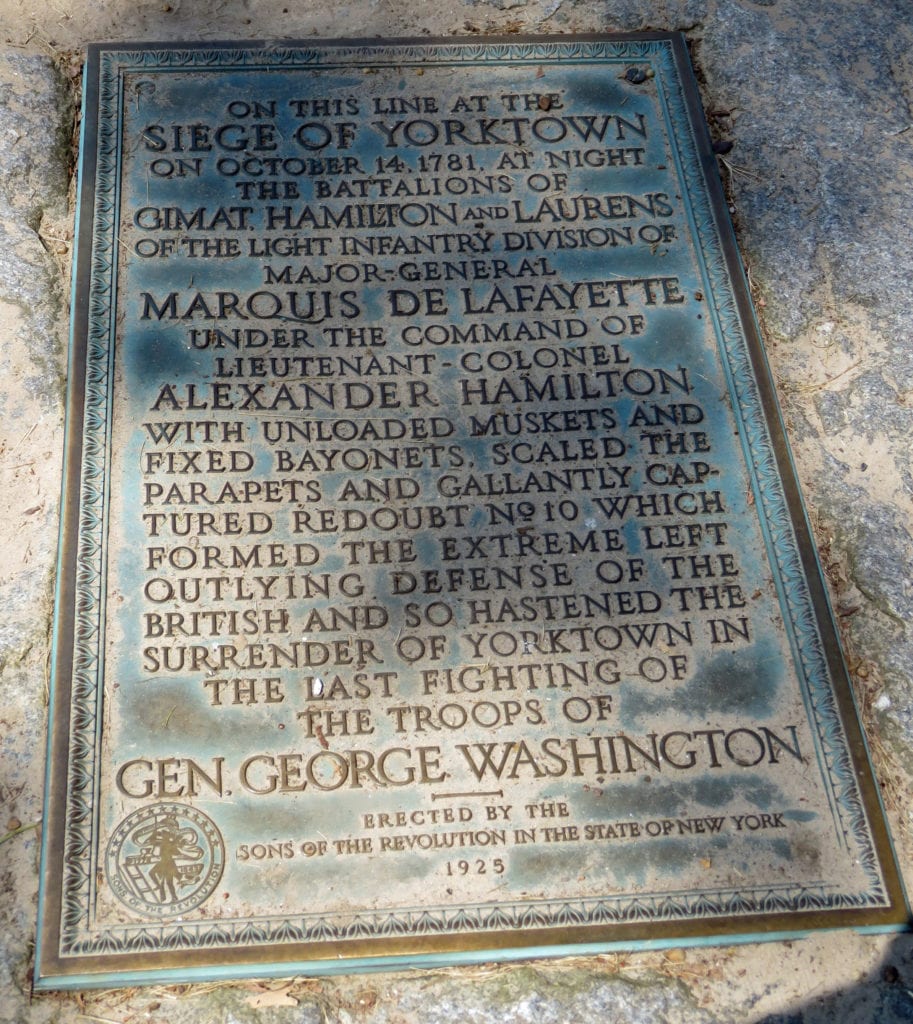

Operating on the belief that Clinton would arrive with reinforcements, Cornwallis confidently remained within Yorktown’s inadequate defenses. Determined that nothing short of outright surrender would suffice, his opponent labored day and night to achieve that end. Washington’s brilliance was on display as he skillfully constricted Cornwallis’s position by digging entrenchments, erecting redoubts and artillery batteries, and launching well-timed attacks to capture key enemy positions. The nearly flawless Allied campaign sealed Cornwallis’s fate. Trapped inside crumbling defenses, he surrendered on October 19, 1781, effectively ending the war in North America.

What struck me on our visit to the Siege at Yorktown battlefield and visitors center was the key role played by luck, timing — and the French.

While historians concede that Cornwallis was a brilliant military commander, his choice of the deep water port on the York River at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay may have sealed his fate. According to sources, the river between York and Gloucester Point averages about 20 feet in depth. Apparently Cornwallis saw it as a place to fortify so the British Navy could get its ships inland to resupply the war effort. But the French Navy also knew about the deep water leading inland to an existing tobacco port.

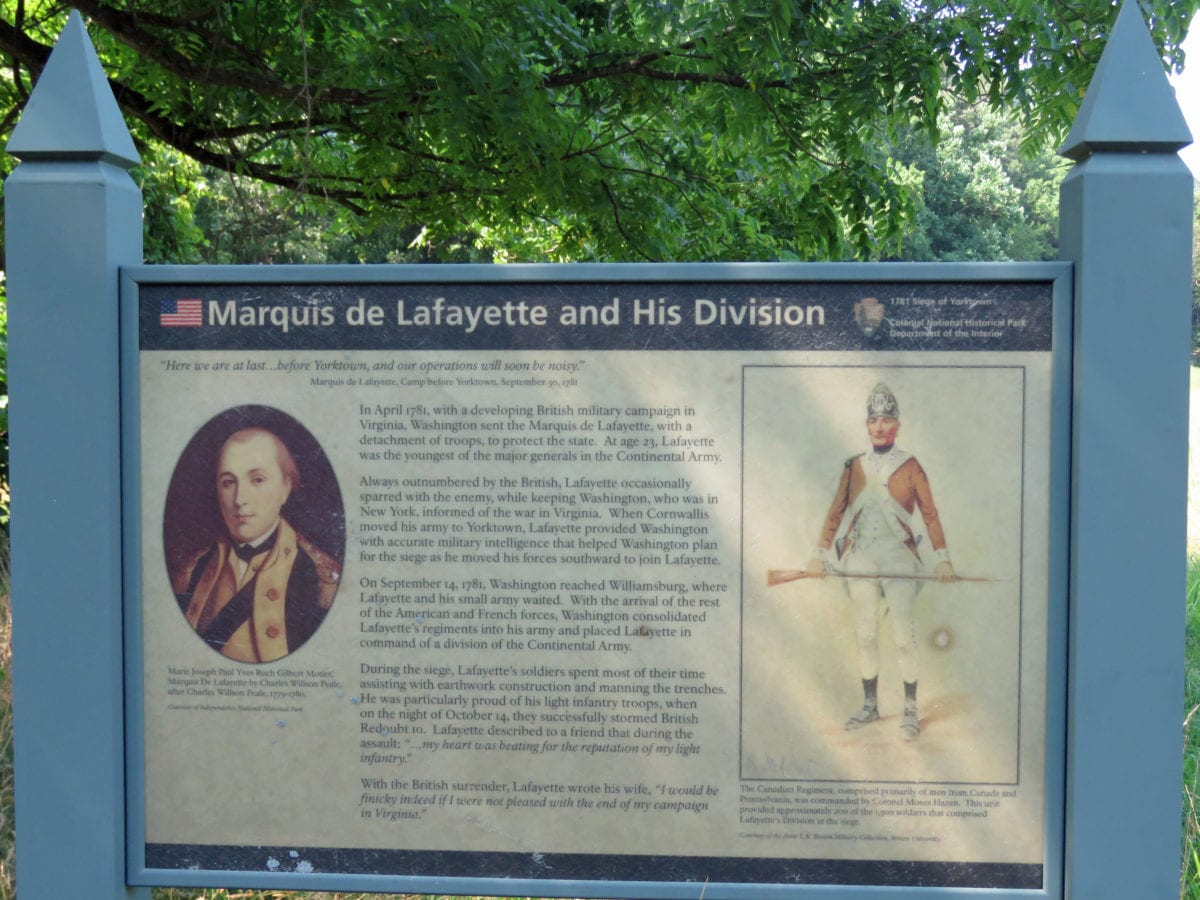

While General Washington was planning an attack on New York City from his positions at Newport, Rhode Island, and Dobbs Ferry, New York, the French Army commander Comte de Rochambeau got word of help on the way from Comte de Grasse, on his way to the Chesapeake to deliver 500,000 silver pesos collected from the citizens of Havana, Cuba, and the government of Spain to fund supplies and payroll for the Continental Army. A Continental Army force led by the Marquis de Lafayette was already shadowing Cornwallis in Williamsburg, Virginia, west of Yorktown, so Washington left a few solders and some cooks behind baking bread to fool Clinton and marched his army to Williamsburg and ultimately Yorktown in the August heat.

Today this is known as the celebrated march, and it pitted a combined force of about 17,000 continental, French and German forces against the 1,500 men left with Cornwallis after they suffered heavy casualties at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse and some reinforcements from New York, leaving Cornwallis with about 7,200 soldiers at his command.

When the siege began in October, the forces of Washington and Rochambeau were able to sneak up on the British on a rainy night and dig in about 150 yards from their position near the river. Over the next few days and weeks, they pounded the British with cannon fire and moved even closer to surround Cornwallis, his only possible escape across the river to Gloucester Point or out into the Atlantic Ocean. Only the French Navy led by Comte de Grasse defeated the British Navy offshore at the Battle of the Capes on September 5, 1781, driving them back to New York and leaving Cornwallis no choice but to surrender or die.

Demoralized, the British led by the mad King George III of the House of Hanover — considered a tyrant by Americans, mentally and physically ill by historians — was forced to the negotiating table and signed the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, the real date of American independence from the British Empire.

It took several more years for the Constitution of the United States to be written and ratified. It was officially signed on September 17, 1787. So it could be argued that is the date that should be celebrated, the day when the United States actually became a true and independent country.

Now the problem is how to keep it.

We survived the War of 1812, the Civil War, World Wars I and II, Korea, Vietnam, wars in Central America, Afghanistan and Iraq. We’ve survived incompetent presidents and do nothing Congresses. Can we survive Trump? This president seems to have so little knowledge of any of this history and wants to meet in person with Vladimir Putin of Russia?

Rather than thumbing our noses at the French, we should be thanking them every Fourth of July. Without the French Army and Navy, we might never have become an independent country. I say “Vive la France” and “Vive la liberté.”

Happy Independence Day. Remember the French.

The Moore House at the Colonial National Historical Park. On October 17, 1781, Lord Cornwallis, realizing the defeat of his army was inevitable, sent a message to General George Washington: “Sir, I propose a cessation of hostilities for twenty-four hours, and that two officers may be appointed by each side, to meet at Mr. Moore’s house, to settle terms for the surrender of the posts of York and Gloucester.” Thus ending for all practical purposes the Revolutionary War and establishing American Independence: Glynn Wilson

This 300 year old road was used by Continental Army General George Washington to approach the British position at Yorktown, Virginia in the summer of 1781: Glynn Wilson

This is one of the few big “witness” trees that might have been there in the fall of 1871 when the British surrendered, ending the American Revolutionary War: Glynn Wilson

A plaque celebrating the American victory over the British at Yorktown, Virginia: Glynn Wilson

Redoubt 10 by the York River where Alexander Hamilton led the forces that captured the ground, closing in and surrounding the British position at Yorktown, Virginia: Glynn Wilson

This is one of the few big “witness” trees that might have been there in the fall of 1871 when the British surrendered, ending the American Revolutionary War: Glynn Wilson

The view from the French position looking across the field toward the British encampment by the York River in Yorktown, Virginia: Glynn Wilson

The view from the British position looking across the field toward the American and French encampments at the Yorktown battlefield: Glynn Wilson

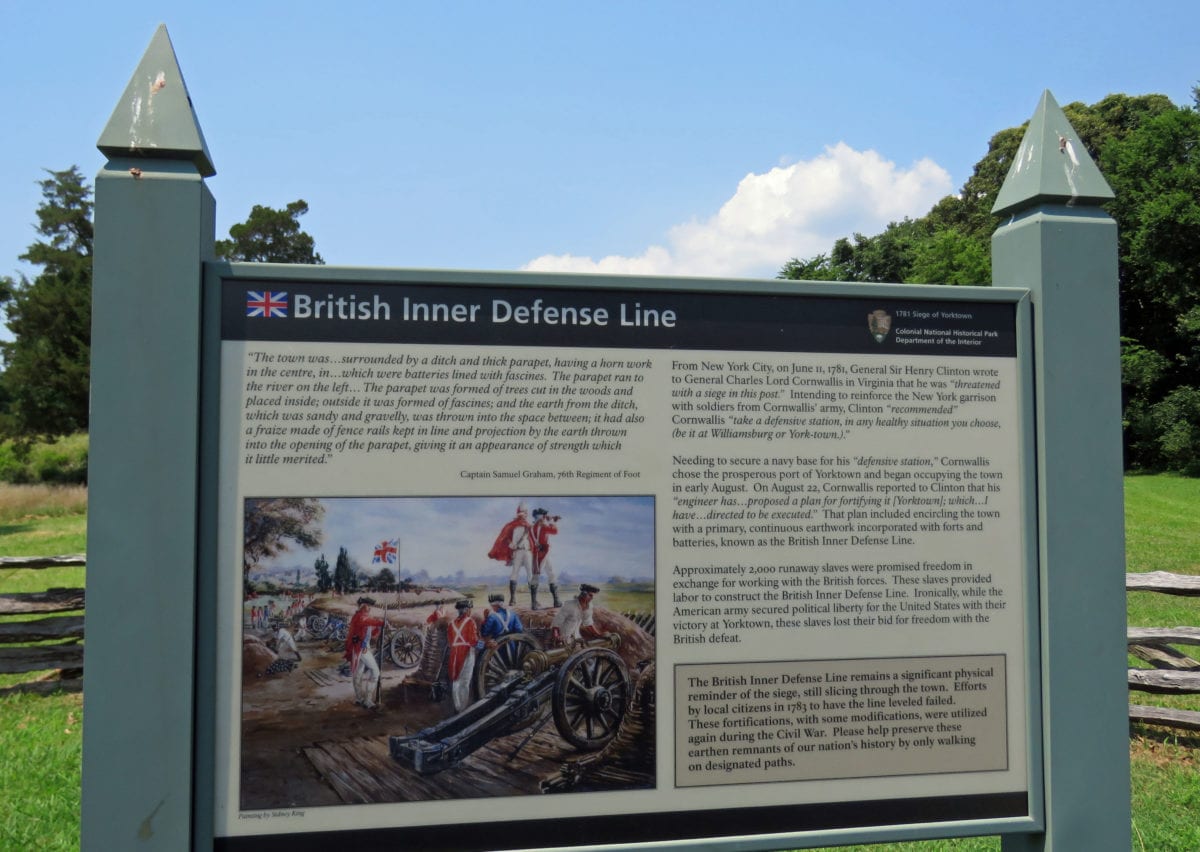

A sign explaining the British position at Yorktown: Glynn Wilson

A National Park Service ranger during a program explaining the events that occurred in the summer and fall of 1781: Glynn Wilson

A sign explaining the French position on the Yorktown battlefield: Glynn Wilson

Americans celebrating freedom and independence on the beach along the York River in Yorktown, Virginia: Glynn Wilson

Text design greeting card for the French National Day, July 14. Vive La France. Long Live France. (More photos below…)