By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Greenbelt National Park just north of the nation’s capital was the scene of a historic gathering of Native Americans, Japanese Buddhist monks and Americans interested in bringing about an era of spiritual peace 40 years ago in the summer of 1978.

David Williams of Santa Barbara California was there. He returned to the park and to Washington on the 40th anniversary in the summer of 2018 to offer a new symbolic peace pole to the occupant of the White House on its way to New York and Jerusalem.

There was no response from the president, which is not surprising since the original movement was also rebuffed by then President Jimmy Carter and Congress, although they were successful with prayers, speeches and drums in defeating 11 pieces of legislation that would have made discrimination against American Indians worse.

According to the Washington Post’s coverage of “The Longest Walk,” more than 1,000 peaceful protesters camped in Greenbelt Park just outside Washington in July, 1978, the final staging point for their ceremonial march on the nation’s capital and eight days of political protests and spiritual observances.

Participants in the march traveled 2,700 miles from Alcatraz off the coast of San Francisco to the National Mall. None of the legislation they opposed made it through Congress to the president’s desk for signing, and it became seen as a historic, non-violent spiritual movement and the first time all the surviving Native American tribes came together in a united spiritual and political action. It is now seen as a precursor to the historic gathering in 2016 at Standing Rock in North Dakota.

The event is recognized on the National Mall history site with a notice that says the American Indian Movement began The Longest Walk in February, 1978. It was a cross-country march beginning on Alcatraz Island in California, “to support tribal rights and bring attention to 11 pieces of legislation before Congress affecting American Indians.” The proposed legislation would have changed some provisions of early treaties on tribal government, hunting and fishing rights, and schools and hospitals. Because of their opposition, at least in part, none of the bills passed.

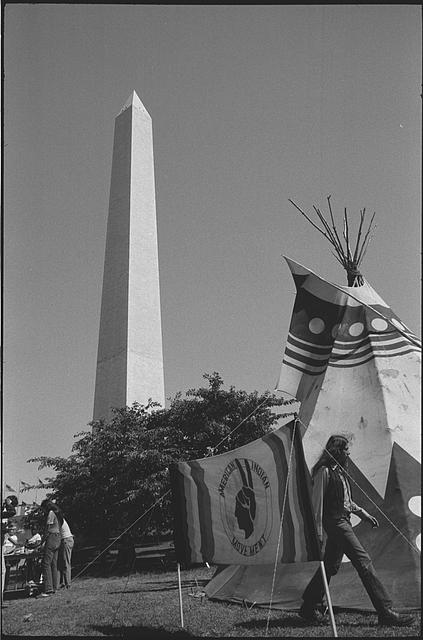

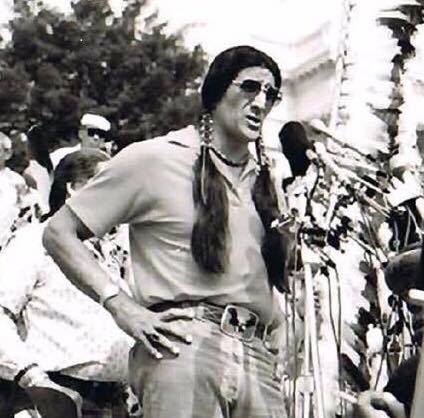

Marchers arrived in July and tribal elders and walk leaders camped in tepees on the grounds of the Washington Monument. Over the course of a week, they held rallies and meetings throughout Washington, including at the Capitol, the Supreme Court and the White House. Later they prepared a written document to outline their concerns, in which they expressed the philosophy that “spirituality is the highest form of politics.”

The U.S. Army and the U.S. Department of the Interior welcomed the group in Greenbelt Park and honored the group’s request for logistical support by setting up field kitchens, water tanks and refrigeration units to accommodate and serve them with fresh drinking water and meals. Medical and extra sanitation facilities at both Greenbelt Park and West Potomac Park were also arranged.

The District of Columbia girded for the procession into the city for a series of rallies, demonstrations and protest marches on the Capitol, the White House, the Supreme Court and the FBI building, where a loose coalition of more than 100 tribes and organizations from across the country protested continuing discrimination.

Headed by spiritual leader and Lakota Sioux Ernie Peters “carrying a sacred pipe packed with ceremonial tobacco,” according to the Post, the procession finished up on Washington Monument grounds.

The bulk of participants rested each night at the Greenbelt Park encampment and came into the city each day by shuttle bus service arranged by the Interior Department, the city and Metro. But about 200 to 300 elders and spiritual leaders remained in a “spiritual camp” in West Potomac Park near the monument grounds in a continuous four-day vigil. A ceremonial fire burned constantly on a special altar surrounded by a ring of 20 to 30 ceremonial tepees.

D.C. Mayor Walter E. Washington signed a proclamation declaring “Longest Walk Day” and officially welcomed the marchers and presented their leaders with a symbolic key to the city.

While “cordiality and cooperation prevailed in much of official Washington, security was beefed up at the Interior Department,” the Post reported. Officials said they had no specific indication of possible trouble, but were mindful of the Indian takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in 1972 during the so-called “Trail of Broken Treaties,” a political action march similar to The Longest Walk and with some of the same leadership.

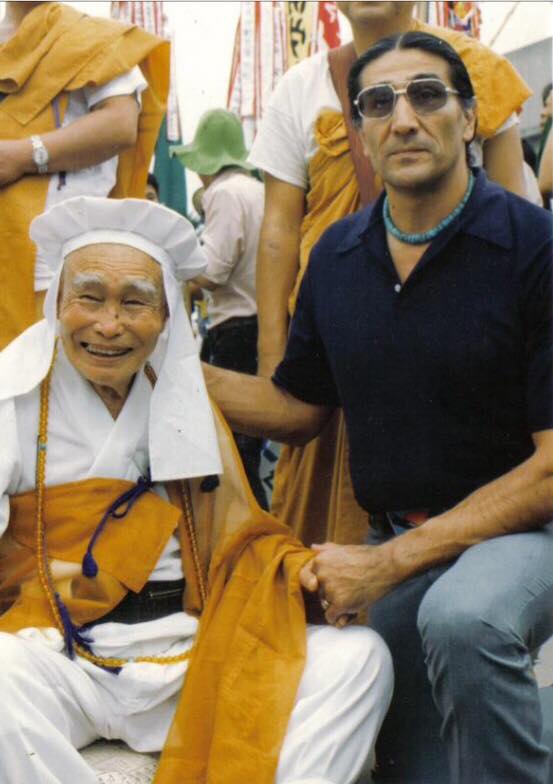

But according to an oral history interview with David Williams, the more militant American Indian Movement was replaced by the inspiration of non-violence from Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. and the marchers were held together on the trek across the country by a group of Japanese Buddhist Monks who chanted, drummed and preached the philosophy of non-violent protest. The founder of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order, Nichidatsu Fujii, joined the movement after finding out that the native tribes and nations in North America were still in existence and had not been totally wiped out by genocide. Marchers called him Fujii Guruji because Gandhi did, according to Williams.

The United Methodist Church donated about $15,000 for food. Longest Walk organizers also raised about $25,000 through the National Council of Churches and unspecified additional amounts through a benefit concert at the Capital Centre on July 23 and a benefit performance of the Indian play “Black Elk Speaks” at the Kennedy Center on Sunday night to help pay travel expenses for Indians going home after The Longest Walk was over.

The event also merited coverage in the New York Times, which pointed out the change in appeal to “brotherhood and conscience” compared to earlier protests.

“Before everything we do, we pray,” Mr. Peters was quoted as saying. “You can’t do anything without thanking the creator for it, and when you are done you give thanks again. You own nothing. You don’t even possess your body; it belongs to mother earth. All you possess your spirit. But the simplest form of energy is there: the energy of the human soul. Spirituality is what this march is all about.”

Not so spiritual, however, is Mr. Peters’s judgment of “the great white father,” according to the Times.

“I don’t expect to go the White House,” the march leader said. “We are asking the country to honor our treaties. Carter can’t do it because the corporations are running him.”

The corporations referred to were mining the oil, gas, coal and uranium under Native American lands in the West, according to the Times, especially of concern to the Navajo in Arizona and New Mexico, and the Northern Cheyenne and the Crow in Montana — a practice that was slowed under the Obama administration but has been accelerated again under the Trump administration.

Back in the day, the controversy over federal government use of land and water in the west — a controversy that continues today — was driven by a coalition called the Interstate Congress for Equal Rights and Responsibilities backed by businessmen, ranchers and fishermen. With 10,000 non‐Indian members in 17 states, that group pushed “white rights,” according to the Times, which called “the stakes … enormous.”

According to a historical post on the website of the Smithsonian’s Museum of the American Indian, activists who came together with marchers for a concert to mark the end of the first Longest Walk included Muhammad Ali, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Floyd Red Crow Westerman, Harold Smith, Stevie Wonder, Marlon Brando, Max Gail, Dick Gregory, Richie Havens and David Amram.

Celebrities support the Longest Walk in Washington, D.C. in 1978: Photo courtesy of David Amran, from IndiVisible: African–Native American Lives in the Americas

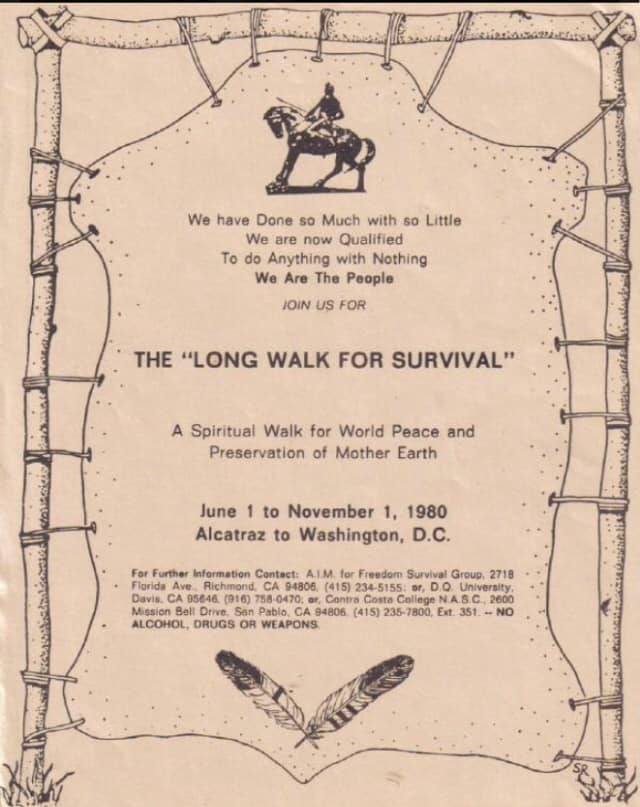

Since the original Longest Walk, there have been six additional major walks. The Long Walk for Survival in 1980 focused on anti-nuclear war issues and environmental problems. But in what came to be called the Longest Walk II, in 2008, the attention was placed on environmental rights and the protection of sacred sites. In 2011 the Longest Walk III focused on reversing diabetes and the health of Indigenous peoples. In 2013 the Longest Walk IV was a return to Alcatraz, and focused on reaffirming Native sovereignty in the United States, recognizing that the Indian nations still exist with inherent rights to govern themselves. Longest Walk V in 2016 culminated at the Lincoln Memorial and focused on drug abuse and domestic violence.

“This ongoing march for Native rights has a direct correlation to the standing of Native people in the United States. From the occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 to 1971 to the Apache-Stronghold today, Native people have a record of contemporary activism directly affecting legislation,” according to the museum. “Protecting who we are as Native people in the United States, however, oftentimes requires more than appeals to government. Honoring our ancestor’s sacrifices means protecting our land, our water, our languages, our cultures, our women, our children, who we are as Native people. Time and time again, Native communities have banded together to take action to defend these inherent, sovereign rights.”

In 2014, the museum opened an exhibit that was more than 10 years in the making on 600 treaties between the federal government and Indian tribes called Nation to Nation, and revealed something counterintuitive to the public perception that the U.S. government broke all the treaties with all the tribes. The curator, Suzan Shown Harjo, a Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee from Oklahoma living on Capitol Hill, said the states were a bigger enemy of the Indians just as they also discriminated against African Americans.

“It’s a story that hasn’t been told,” she said. “Our treaties haven’t been broken. They’ve been stretched and stretched to the breaking point.”

During the Long Walk for Survival in 1980, Williams and his friend Wave from the Rainbow Gathering fashioned a peace pole in Greenbelt Park that has traveled to many gatherings around the country. That pole eventually deteriorated and was retired in a fire, so Williams has constructed another peace pole he plans to take all the way to Jerusalem in an effort to unite the world’s religions behind the spiritual peace movement.

“The idea is this stands for a message of peace, depicted by six symbols of various cultures,” Williams said. “It symbolizes the natural law, the Iroquois Great Law of Peace, renouncing violence and warfare … to bring harmony to the people.”

He says it was in part the basis for how American democracy was formed based on natural law. Although the peace part was left out because the new United States government had to fight a war for independence against Great Britain to form the new country.

The peace pole also incorporates the philosophy of peace from Buddhism, the Hopi Declaration of Peace, and similar messages from other Native American cultures.

Williams set up the new peace pole in Lafayette Square Park in August and offered a prayer to try and get the White House to embrace it.

Wave and David Williams drum and chant for peace in Lafayette Square Park by the White House in August, 2018: Glynn Wilson

Watch the video on Facebook here.

Other Links –

A UPI story on the Longest Walk from the Santa Barbara News Press.

More Photos –

Thanks for this great Article Glynn!

18min (starting at ~53:00) Mutiny Radio SF Diamond Dave Whitaker with Common Thread Collective Sept7 interviews David Williams with Great Spirit Relay Report, and Glynn Wilson of the New American Journal discussing his Sept7 News Article about the New Peace Pole for the White House and a history of the 1978 Longest Walk, the 1980 Long Walk for Survival and the 2018 Great Spirit Relay which all camped in Greenbelt National Park, podcast recording:

http://podcasts.pcrcollective.org/CommonThreadCollective/CommonThreadCollective-20180907.mp3

American Peace Movement

Great Spirit All Our Relations

Relay of Peace Through Love

2018 Global Peace Council

Greenbelt National Park

October 24-31, 2018

Sweetgum Parking Lot

Free Speech Picnic Area

Daily 10am-2pm

Peace March to the White House

Departs Sweetgum 9:11am Nov1

11 mi to David’s Tent DC on Capitol Mall, 1.3 mi from there to White House Lafayette Plaza

Global Peace Council Camps

Advance Teams, Scout Camps, setting up from Sept.14, 2018

http://global-emergency-alert-response.net/GlobalPeaceCouncil.html

I have a government and economics book which has some pictures of the longest walk in which my grandfather is in the picture.