By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. – If ever there lived a scientist who came closest to figuring out the essence of human nature and what we need to do to survive on planet Earth, it was Edward Osborne Wilson from Birmingham, Alabama, who reached the zenith of the biological sciences at Harvard and provided the research needed to answer some of our most pressing questions in human evolution. Considered by many to be the modern heir of Charles Darwin, Dr. Wilson died on Sunday in Burlington, Massachusetts less than six months after the passing of his wife of 66 years, Irene. He was 92.

His death was announced on Monday by the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation without listing a cause.

“(We are) deeply saddened to share the passing of preeminent scientist, naturalist, author, teacher, and our inspiration, Edward O. Wilson, Ph.D. One of the most distinguished and recognized American scientists in modern history, Dr. Wilson devoted his life to studying the natural world and inspiring others to care for it as he did,” the group said in statement announcing his death.

“Ed’s holy grail was the sheer delight of the pursuit of knowledge. A relentless synthesizer of ideas, his courageous scientific focus and poetic voice transformed our way of understanding ourselves and our planet,” said Paula J. Ehrlich, CEO and President of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and co-founder of the Half-Earth Project, resolving to set aside half the planet for wildlife species to survive and continue evolving.

“His greatest hope was that students everywhere share his passion for discovery as the ultimate scientific foundation for future stewardship of our planet,” he said. “His gift was a deep belief in people and our shared human resolve to save the natural world.”

Called “Darwin’s natural heir,” Wilson was known affectionately as “the ant man” for his pioneering work as an entomologist. Dr. Wilson was Honorary Curator in Entomology and University Research Professor Emeritus at Harvard University, Chairman of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation Board of Advisors, and Chairman of the Half-Earth Council.

Beloved by his students throughout the world and at Harvard University where he taught, Dr. Wilson was also an advisor to the world’s preeminent scientific and conservation organizations, the foundation says. He was the author of over 30 books and hundreds of scientific papers, creator of scientific disciplines including sociobiology and evolutionary biology and evolutionary psychology, and advances in global conservation, including “Half-Earth.”

Dr. Wilson was honored with over 100 prizes in his life including the U.S. National Medal of Science, the Crafoord Prize, and was awarded two Pulitzer Prizes for books, including On Human Nature published in 1978, which dealt with the role of biology in the evolution of human culture.

“It would be hard to understate Ed’s scientific achievements, but his impact extends to every facet of society. He was a true visionary with a unique ability to inspire and galvanize,” said David J. Prend, Chairman of the Board, E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation. “He articulated, perhaps better than anyone, what it means to be human. His infectious curiosity and creativity have shaped the lives of so many, myself included, and I feel lucky to have called him a friend.”

“It is a rare combination of good when an intellectual giant like Ed Wilson can leave a legacy of enormous scientific contributions with a memory trail of a kind, humble, generous man who had great exuberance for life,” said Paul Simon, a friend and member of the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation board.

A tribute to Dr. Wilson’s life is planned for 2022. Memorial details are to be announced.

Wilson’s Importance

Scientists, social scientists and students of both are always on the lookout for a grand theory of everything, and Wilson came about as close as you can come in this short summary of how humans evolve and compete as individuals and in groups. While it has not been fully realized in the social sciences yet or recognized in American journalism, this is the key information we need to focus on to fix our communications system so we might survive the era of chaos and confusion we’re living in today.

Our very survival as a species may very well depend on it. He even went out and discovered the math that backs it up.

This may sound like scientific gibberish, but to a journalist and communications researcher who has studied sociobiology, this seems profound to me, with great implications for creating a shared narrative and a successful democratic political system.

“In a group, selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals,” Wilson argued. “But, groups of altruistic individuals beat groups of selfish individuals. Competition between groups selects for pro-social groups. Competition within groups tend to undermine groups. The rest is commentary.”

“People must have a tribe,” Wilson explained. “Experiments conducted over many years by social psychologists have revealed how swiftly and decisively people divide into groups, and then discriminate in favor of the one to which they belong.”

If this doesn’t explain our current predicament, what can? Many commentators have talked about this in terms of “tribalism.”

Related Stories:

Part I: Can Altruism Trump Selfishness to Save Democracy and Planet Earth?

Part II: How Existential Anxiety Leads to Authoritarianism

Part III: How to Create a Functioning Communications System to Save Democracy and the Planet

Dr. Wilson’s legacy for the study of human nature is of course an unfinished story, according The New York Times version of his news feature obituary. That is true. Science is always evolving. That’s the nature of scientific inquiry.

His Wikipedia page is also an unfinished story.

“Scientists are a long way from Dr. Wilson’s dream of an evolution-based account of human nature,” wrote Carl Zimmer in The Times.

Critics said similar things about Darwin, who was attacked upon his publication of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, but he is still considered one of the most important scientists and theorists in any science.

Wilson was named one of Time magazine’s 25 Most Influential People in America in 1995, the year I completed my Master’s thesis and was awarded the degree.

In the sciences and social sciences, which Wilson attempted to bring closer together in his book Consilience published in 1994 not long after I met him for the first time at the University of Alabama, Wilson started down a path that crossed directly over my own research agenda and later spawned Evolutionary Psychology in the social sciences as well as Evolutionary Biology in the hard sciences. It all came out of his book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, published in 1975, which was highly controversial at the time.

Wilson set out to apply his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates, and in the last chapter, to humans. He had the unmitigated gall to suggest that evolution and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organization among humans. He was shouted at in public and had a protester pour water on him at one public gathering for it, which generated a fair amount of publicity — and in a way helped to make him more famous than other scientists at the time.

By the late 1980s, objections to this line of thinking from evangelical Christians like Paul E. Rothrock led him to say : “… sociobiology has the potential of becoming a religion of scientific materialism.”

For my money that would beat the hell out of the involvement of religion in American politics and anti-democratic propaganda of our age, unless people want to see a self-fulfilling prophesy come about — the end of American democracy and the end of human life on planet Earth.

As Wilson often said, there is no question that the ants will survive to take over the world when we are long gone from the scene.

“They already have,” he liked to say, pointing out how much of the Earth’s surface they cover, compared to us.

It’s our survival that is at stake, and we are running out of time.

Encountering Wilson

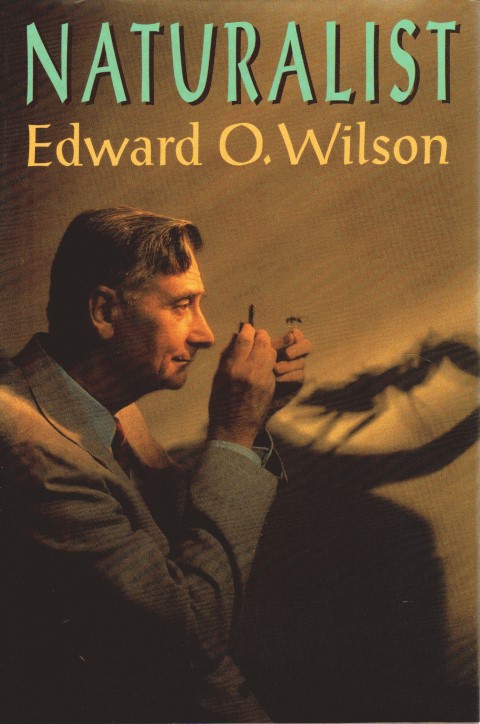

My first encounter with Wilson came in 1994, 27 years ago, the year he published his popular memoir, Naturalist. I had just been accepted into the master’s graduate program in journalism and communications at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, where Wilson did his undergraduate work in biology many years before. My specialty was media influence on public opinion, especially on the science of the natural environment.

In a shrewd bit of public relations, Gorgas Library announced that Wilson’s book would be the one millionth book purchased by the library in its long history. They held a book signing on a gorgeous spring day on The Quad, the famous quadrangle-shaped park at the heart of the capstone campus where Denny Chimes is located.

I asked around and decided I must go to meet this famous man named Wilson and read him for myself. We talked a little while he signed my copy, and I smiled and almost laughed out loud when he drew a little ant by his name. I still have that book. I also got him to sign The Diversity of Life, published in 1992.

Needless to say I was impressed by his story, crossing so many of the same paths as mine from Birmingham to Mobile, Perdido Bay, Baldwin County, Alabama, and the Gulf Coast, where I specialized in covering the environment for a chain of newspapers in the late 1980s and early 1990s. So I sought out his other work and wrote him a thoughtful letter.

He replied and was gracious with his thoughts and advice to a graduate student. I thought of him again while teaching full time in Georgia, and wrote him an email message in the early days of the internet. It was printed out for him by his secretary at the Zoology Museum at Harvard, and he called me back to discuss my questions on the phone — making the excuse that the answers might be too long to dictate and type.

I tell the story in my memoir, Jump On The Bus: Make Democracy Work Again. He hinted that in my writing and creating publications for the web, which I was thinking about even then, I should find a way to “make it Southern.”

I took his advice later, a couple of years into a Ph.D. program at the University of Tennessee, when I worked to create one of the first online magazines, The Southerner. It was a little ahead of its time.

I’ve long had a nagging question he never answered: What happened to him in East Tennessee that made him transfer to Harvard? Many musicians left for New York or Nashville. I experienced my own departure for New Orleans (see my book).

Perhaps some of his research caught the eye of someone in Cambridge, or maybe he had a problem with his faculty committee at Tennessee? I asked him once and he dodged the question, probably in a fit of character and class, not wanting to step on any toes even from his hieghts.

In any event, “Dr. Wilson also became a pioneer in the study of biological diversity, developing a mathematical approach to questions about why different places have different numbers of species,” The Times points out. “Later in his career, he became one of the world’s leading voices for the protection of endangered wildlife.”

A professor for 46 years at Harvard, Dr. Wilson was famous for his “shy demeanor” and “gentle Southern charm,” they say. Yet that hid a fierce determination. By his own admission, he was “roused by the amphetamine of ambition.”

His ambitions put him at loggerhead with other scientists, most notably Richard Dawkins, Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould, and he had other critics, which he seemed to vanquish in 2012 when the math came out in The Social Conquest of Earth.

“But while his legacy may be complicated, it remains profound,” The Times admits.

“He was a visionary on multiple fronts,” said Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, a former student of Dr. Wilson’s and a professor emerita at the University of California, Davis, in an interview in 2019.

“His courageous scientific focus and poetic voice transformed our way of understanding ourselves and our planet,” Ehrlich said.

I found the book in the library at the University of Tennessee in 1996, and studied it in depth, even making margin notes and quoting it in my dissertation. But it was still controversial among the faculty there.

Personal Background

E.O. Wilson was born in Birmingham, Ala., on June 10, 1929, the year of the stock market crash and beginning of the Great Depression. His father, Edward Osborne Wilson Sr., worked as an accountant. His mother, Inez Linnette Freeman, was a secretary. They split up when he was only 8.

As his parents’ marriage fell apart, he writes that he found solace in forests and tidal pools.

“Animals and plants I could count on,” Dr. Wilson wrote in his 1994 memoir, Naturalist. “Human relationships were more difficult.” Man you can say that again.

One day, as he was casting a fishing line on the Gulf Coast, he pulled too hard when he caught a pinfish, it flew into his face, and one of the spines on its fin pierced his right eye, leaving him partly blind.

“The attention of my surviving eye turned to the ground,” Dr. Wilson wrote.

He developed an interest in ants. It became his life’s obsession.

Uncovering logs and discovering ant nests felt to him like exposing a strange netherworld. In high school, he discovered the first colony of imported fire ants in the United States — a species that went on to become a major pest in the South.

At the time, he was also undergoing a spiritual transformation. Raised as a Baptist, he struggled with prayer. During his baptism, he became keenly aware that he felt no transcendence. “And something small somewhere cracked,” Dr. Wilson wrote. So he drifted away from the church, much as I did.

“I had discovered that what I most loved on the planet, which was life on the planet, made sense only in terms of evolution and the idea of natural selection,” Dr. Wilson later told the historian Ullica Segerstrale, “and that this was a far more interesting, richer and more powerful explanation than the teachings of the New Testament.”

Dr. Wilson earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology at the University of Alabama, where he studied dacetine ants, a species native to the American South.

“They are under the microscope among the most aesthetically pleasing of all insects,” he later wrote in his memoir.

In 1950, Dr. Wilson went to Harvard to earn his Ph.D. To further his graduate work, he embarked on a long journey in 1953 to explore the global diversity of ants, starting in Cuba and moving on to Mexico, New Guinea and remote islands in the South Pacific.

Among other things, Dr. Wilson studied the geographical ranges of ant species, looking for clues to how they spread from place to place, and how old species gave rise to new ones. “Evolutionary biology always yields patterns if you look hard enough,” he wrote.

Returning from his travels, Dr. Wilson met Irene Kelley of Boston. They married in 1955. She died in August. They are survived by their daughter, Catherine I. Gargillm.

Dr. Wilson joined the Harvard faculty in 1956. As a new professor, he quickly began pursuing a number of scientific questions at once. In one line of research, he searched for a theory that could make predictions about the diversity of life.

As Dr. Wilson was developing the theory of island biogeography on the islands of the Caribbean, he was also investigating another deep question: How did the behaviors of different species evolve?

Ants were a good place to start addressing that question.

A self-described “congenital synthesizer,” Dr. Wilson began drawing together the theoretical work by other researchers….

If he could explain the behavior of ants, Dr. Wilson reasoned, he ought to be able to explain the behavior of other animals: iguanas, newts, sea gulls — maybe even people.

Dr. Wilson and like-minded colleagues came to refer to this project by a word that had been floating around the animal-behavior world since the 1950s: sociobiology. In 1975, Dr. Wilson published Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. It would become his most controversial book.

“The organism is only DNA’s way of making more DNA,” Dr. Wilson brashly declared. He then explored a huge range of behaviors, showing how they might be the product of natural selection.

“It showed how this applies to virtually everything we see out there in the world of animal behavior, in a way that nothing had even come remotely close to doing,” Lee Dugatkin, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Louisville and the author of Principles of Animal Behavior, a widely used textbook, said in a 2019 interview.

At first, “Sociobiology” was showered with praise and attention. An article about it landed on the front page of The New York Times on May 28, 1975. In Scientific American, the Princeton biologist John Tyler Bonner called it “an extraordinary beginning.” Dr. Bonner wrote that Dr. Wilson “has identified and brought together in one tome all those elements that will be the ingredients of sociobiology in the future.”

Then, Dr. Wilson later recalled in his memoir, “Everything spun out of control.”

Dr. Wilson got in trouble for extending sociobiology to humans.

He seemed to load the scales of influence on human behavior down on the quantitative side of nature, instead of the qualitative side of nurture, where it had landed in the age of Post Modernism.

He had invited his readers to consider how human nature might be shaped by evolutionary pressures. He warned them that this would not be easy: It would be hard to tease apart the effects of human culture from those of natural selection. Making matters worse, no one at the time had linked any genetic variant to any particular human behavior.

“There is a need for a discipline of anthropological genetics,” he wrote.

Nevertheless, Dr. Wilson argued that our species had a propensity to behave in certain ways and form certain social structures. He called that propensity human nature.

Natural selection could help explain psychology, in other words. Human aggression, for example, may have been adaptive for early humans.

“The lesson for man is that personal happiness has very little to do with all this,” he wrote. “It is possible to be unhappy and very adaptive.”

Dr. Wilson’s critics ignored these caveats. In a letter to The New York Review of Books, some denounced sociobiology as an attempt to reinvigorate tired old theories of biological determinism — theories, they claimed, that “provided an important basis for the enactment of sterilization laws and restrictive immigration laws by the United States between 1910 and 1930 and also for the eugenics policies which led to the establishment of gas chambers in Nazi Germany.”

In her book Defenders of the Truth (2000), Dr. Segerstrale wrote that Dr. Wilson’s critics had shown “an astounding disregard” for what he had written, arguing that they had used “Sociobiology” as an opportunity to promote their own agendas. When Dr. Wilson attended a 1978 debate about sociobiology, protesters rushed the stage shouting, “Racist Wilson, you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide!” A woman dumped ice water on him, shouting, “Wilson, you are all wet!”

After drying himself off with paper towels, Dr. Wilson went ahead and gave his speech.

In that speech and elsewhere, Dr. Wilson declared that sociobiology offered no excuse for racism or sexism. He dismissed attacks against him as “self-righteous vigilantism.” And he went on to dig even deeper into the evolution of human behavior.

The legacy of “Sociobiology” was profound for researchers who study animals.

“It was liberating,” Karen Strier, a primatologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the president of the International Primatological Society, said in an interview. “You can study all animals with the same basic perspective.”

Animal behavior today is “95 percent sociobiology,” said Dr. Hrdy, who, after studying with Dr. Wilson at Harvard, went on to publish influential studies about how female primates behave in subtle, complex ways to increase their reproductive success.

A Busy Retirement

In the 1980s, Dr. Wilson began the third great project of his career, as a champion of the world’s wild places. By then, his earlier work on island biogeography was taking on a terrifying new importance. As humankind reduced rain forests and other habitats to fragments, countless species were being pushed toward extinction.

Dr. Wilson took up the dangers of extinction in his best-selling 1992 book, The Diversity of Life.

Dr. Wilson wove accounts of his travels in the tropics with the latest understanding about humanity’s impact on the biological richness of the planet. “Earth has at last acquired a force that can break the crucible of biodiversity,” he wrote.

Dr. Wilson retired from Harvard in 2002 at age 73, although that transition is hard to recognize from his résumé. After stepping down, he published more than a dozen books, including a digital biology textbook for the iPad.

Retirement did not stop him from championing new ideas, including some that outraged some of his colleagues.

In 2010, he turned against inclusive fitness, publishing a paper attacking the concept with Martin A. Nowak of Harvard and Corina E. Tarnita, now at Princeton. Dr. Wilson later popularized their argument in his 2012 book, The Social Conquest of Earth.

“The basic foundations of inclusive fitness theory are unsound,” Dr. Wilson said in a 2012 interview. Instead, he and his colleagues argued, biologists should look to other forms of evolution to explain altruism and other puzzling forms of behavior. Natural selection acting on individuals could explain some; it was possible that groups of animals could be selected as well.

Dr. Wilson dismissed his critics, likening them to early astronomers who came up with elaborate explanations to support their idea that the sun and planets revolved around the earth.

In retirement, Dr. Wilson continued to use his fame to draw attention to biodiversity. In 2008 he unveiled the Encyclopedia of Life, a website that will eventually house information about every known species.

Dr. Wilson continued to warn of the dangers of an impending mass extinction, but he did not consider the planet doomed.

“I’m optimistic,” he said in an interview in 2012. “I think we can pass from conquerors to stewards.”

In his 2016 book, Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life, he argued that the only way to avoid a mass extinction would be to leave half the earth wild.

Like so many of Dr. Wilson’s ideas, it spurred other scientists to do more research of their own. In 2018, Dr. Pimm and his colleagues published a study showing that a careful plan for deciding which places to preserve could make Dr. Wilson’s vision a reality.

“First, he is a towering example of a specialist, a world authority; nobody in the world has ever known as much as Ed Wilson about ants,” said David Attenborough, the BBC film maker. “But in addition to that intense knowledge and understanding, he has the widest of pictures. He sees the planet and the natural world that it contains in amazing detail but extraordinary coherence. And he has the ability as a writer to convey to all of us, specialists and non-specialists alike, why this is not only beautiful and moving and irreplaceable, but essential for our sanity.”

It is also essential for our survival.

Other’s who knew Dr. Wilson are publishing their thoughts in places like the comments section on the BioDiversity Foundation website.

“A stately tree has fallen in the forest, but the generations of naturalists and scientists Ed inspired will help to fill the massive gap and forever be his legacy,” wrote Diane Davidson. “It is perhaps a blessing that he left this world before all the consequences of climate change and habitat destruction – which he so fervently and effectively oppose – are fully manifest.”

“We will be forever grateful for his support in our struggle to end logging on public lands here in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” wrote Don Ogden.

Edward wrote “… we must save at least half of the Earth from industrial exploitation …to avoid catastrophic plant and animal extinctions. [Bill H897*] would make us the first state to give this protection to all of its public lands. I strongly support this bill. This is the single most important action the people of the state can take to preserve our natural heritage.”

Alabama Public Television show host Doug Phillips, who first interviewed Wilson back in the 1990s for an episode of the outdoor history show “Discovering Alabama” in part based on research and questions I worked on as a graduate research assistant for the show, issued a statement upon learning of Wilson’s death.

“Farewell to my dear friend Ed Wilson, champion for the Creation and fellow advocate for the Alabama Wilds. I will miss the many enjoyable excursions with him in the Alabama backcountry and will always be humbled by his gracious participation with Discovering Alabama,” Phillips said.

“In special remembrance, Discovering Alabama will again feature the renowned Alabama native, Dr. E.O. Wilson, in our upcoming show ‘Animal Friends’,” he added, “a fitting subject for his legacy of environmental leadership, and sadly, Discovering Alabama’s last opportunity to be blessed with his presence.”

___

More quotes will be added as they come in… feel free to add thoughts in the comments.

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal.

I’ve written other things about Wilson over the years, and even asked the head of the Alabama Baptist Convention about one of his books and ideas: http://blog.locustfork.net/2011/08/is-a-great-compromise-between-science-and-religion-possible/

Excellent Article Glynn! Thanks.