James Webb Space Telescope Captures New Images of the Cosmos. Photos sent back showed nebulas, a galactic cluster and possible water vapor on an exoplanet: NASA

The Big Picture –

By Glynn Wilson –

For some reason I had a little trouble falling sound asleep on Saturday night. So after watching a couple of shows on Netflix, dozing off a few times and waking back up, I went outside for a few minutes for some fresh air between 1 and 2 a.m. It was deathly quiet in the campground, and very dark in this forest.

All the other campers must have been asleep by then, some over by the creek listening to the babbling brook in their dreams. There is one nearly round opening in the trees here where you can see the night sky a little. There was one bright star in the center of it all. The moon was off to the side behind the trees and a light layer of clouds. I could barely make out the purple outline of the Milky Way Galaxy, and I was thinking about those first images of deep space from the Webb Space Telescope released by NASA this week.

In my head I kept hearing the voice of Carl Sagan, who you may recall often talked about the “billions, and billions of stars” in the universe.

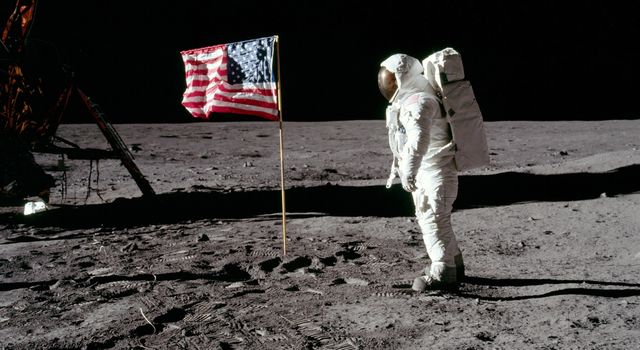

I thought back to that night on July 20, 1969 — 53 years ago this week — when my dad recorded the moon landing on a home movie camera off the screen of our RCA television set in the suburbs of Birmingham, Alabama. All politics aside, along with personal grievances, the people of the world came together on that night and watched the same remarkable thing, human beings walking on the moon.

What they witnessed was Astronaut Buzz Aldrin planting a flag on the surface of the moon, an American flag. It was a moment to be proud to be an American. We beat the evil Russians to the moon.

What happened to us after that? It was the last moment when the people of the United States were together on anything, and the last time the people of the world came together on anything.

And with all the gloating by scientists at NASA headquarters in Greenbelt, Maryland and elsewhere, the images didn’t seem to make even the smallest dent in our political divide. If fact, a huge proportion of the population probably think the images are fake, just like those who thought the moon landing was staged in some Hollywood studio.

Reading the New York Times coverage of the event, you would think everyone in the world agrees about the age of the universe. Unfortunately, a political majority in this country still do not. And they now hold sway even on the United States Supreme Court.

But just for the record here, for this amazing web archive of everything that’s happened in the world of consequence and my world for the past 17 years, let’s explore the actual facts as scientists have been able to ascertain them.

Around 13.8 billion years ago, scientists estimate, what we now call the “universe” was born from darknes in a massive explosion.

“Even after the first stars and galaxies blazed into existence a few hundred million years later, these too stayed dark,” the Times reports. “Their brilliant light, stretched by time and the expanding cosmos, dimmed into the infrared, rendering them — and other clues to our beginnings — inaccessible to every eye and instrument.”

That is until now.

This past Tuesday, when the people in this part of Maryland were experiencing damaging straight line winds of up to 90 mph, which knocked out so many trees in Greenbelt National Park that it had to be closed for the rest of the month, images starting coming in from the James Webb Space Telescope, the most powerful space observatory ever built.

It “offered a spectacular slide show of our previously invisible nascent cosmos,” according to The Times. “Ancient galaxies carpeting the sky like jewels on black velvet. Fledgling stars shining out from deep within cumulus clouds of interstellar dust. Hints of water vapor in the atmosphere of a remote exoplanet.”

The event was called “a new vision of the universe” and “a view of the universe as it once appeared.”

“That was always out there,” said Jane Rigby, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and the telescope’s operations manager. “We just had to build a telescope to go see what was there.”

NASA’s successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which took 30 years and nearly $10 billion to build, is equipped to literally show cosmic history. It is a collaboration with NASA, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, and will show us the first stars and galaxies, and search for other potentially habitable worlds, for when we exhaust the livability of this one called planet Earth.

“We’re looking for the first things to come out of the Big Bang,” said John Mather, senior project scientist for the telescope.

The image of a distant star cluster called SMACS 0723, revealed the presence of still more-distant galaxies splayed across the sky. The light from those galaxies, magnified into visibility by the gravitational field of the cluster of stars, originated more than 13 billion years ago.

Believe it. Or not.

“To look outward into space is to peer into the past,” as the Times reported. “Light travels at a constant 186,000 miles per second, or close to six trillion miles per year, through the vacuum of space. To observe a star 10 light-years away is to see it as it existed 10 years ago, when the light left its surface. The farther away a star or galaxy lies, the older it is, making every telescope a kind of time machine.”

Astronomers theorize that the most distant, earliest stars may be unlike the stars we see today. The first stars were composed of pure hydrogen and helium left over from the Big Bang, and they could grow far more massive than the sun — and then collapse quickly and violently into supermassive black holes of the kind that now populate the centers of most galaxies.

The new pictures were rolled out during an hourlong ceremony at the Goddard Space Flight Center that was hosted by Michelle Thaller, the center’s assistant director for science communication, with video stops around the world.

A few miles away at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, an overflow crowd of astronomers whooped and hollered, oohed and aahed, as new images flashed on the screen — evidence that their telescope was working even better than hoped.

One infrared skyscape showed Stephan’s Quintet, five galaxies packed improbably tightly in the constellation Pegasus. Four are so closely engaged in a gravitational dance that they will eventually merge. Indeed, the image revealed a band of dust that was being heated up as two of the galaxies ripped stars from each other.

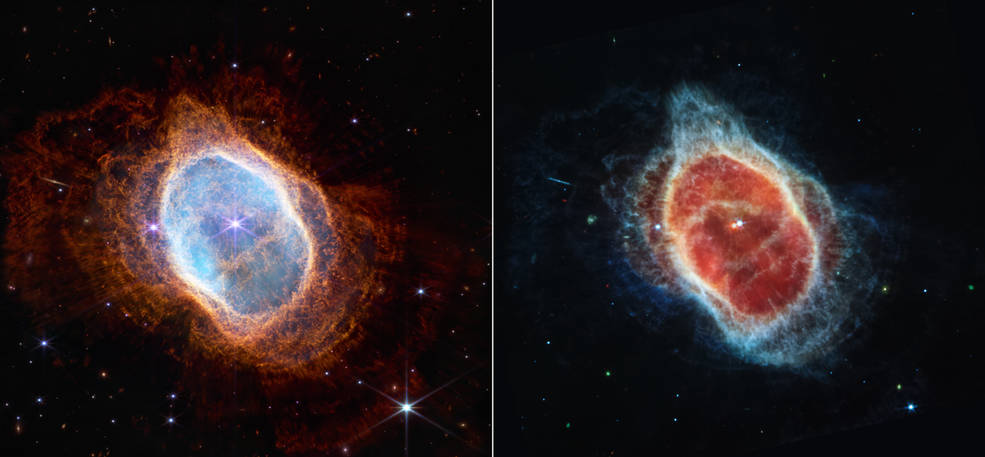

A view of the Southern Ring nebula, the remnants of an exploded star, revealed hints of complex carbon molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, floating in its midst. Such molecules drift through space, settling in clouds that then give birth to new stars, planets, asteroids — and whatever life might subsequently sprout.

“Possibly, the formation of PAHs in these stars is a very important part of how life got started,” said Bruce Balick, an emeritus professor of astronomy at the University of Washington. “I’m gobsmacked.”

This side-by-side comparison shows observations of the Southern Ring Nebula in near-infrared light, at left, and mid-infrared light, at right, from NASA’s Webb Telescope: NASA

Perhaps the most striking image was of the Carina nebula, a vast, swirling cloud of dust that is both a star nursery and home to some of the most luminous and explosive stars in the Milky Way. Seen in infrared, the nebula resembled a looming, eroded coastal cliff dotted with hundreds of stars that astronomers had never seen before.

“It took me awhile to figure out what to call out in this image,” Amber Straughn, deputy project scientist for the telescope, said as she pointed to a craggy structure.

Dr. Straughn added that she could not help thinking about the scale of the nebula, full of stars with planets of their own.

“We humans really are connected to the universe,” she said. “We’re made out of the same stuff in this landscape.”

From astronomers and at watch parties around the globe, there was uniform relief and praise.

“This event blew me away,” said Alan Dressler, an astronomer at the Carnegie Observatory who was instrumental in planning for the telescope 30 years ago. “Guess I’m not as jaded as I thought.”

“The growth in our understanding of the universe will be as great as it was with the Hubble, and that is really saying something,” he added. “We’re in for a great adventure.”

The pictures and other data released on Tuesday were selected by a small team of imaging experts and public outreach specialists for the images’ ability to show off the new telescope’s range and power — and ostensibly to reach the public attention and imagination in a new way. It’s not clear it worked.

Over the next six months, more images will be revealed, along with the results of scientific studies based on them.

Now that the images are out, “there will be an astronomer feeding frenzy!” Garth Illingworth, a researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and an initiator of the telescope program four decades ago, wrote in an email.

The Early Release Science Programs, intended to jump-start the Webb era, include studies of the solar system, galaxies, intergalactic space, massive black holes and the evolution of stars.

Jupiter and its myriad intriguing satellites, such as Europa, the target of an upcoming NASA mission, will be one focus. Two other studies will be devoted to exoplanets, including the Trappist-1 system, just 40 light-years away, where seven planets circle a dim red-dwarf star. Three of those planets are Earth-size rocks orbiting in the habitable zone, where water could exist on the surface.

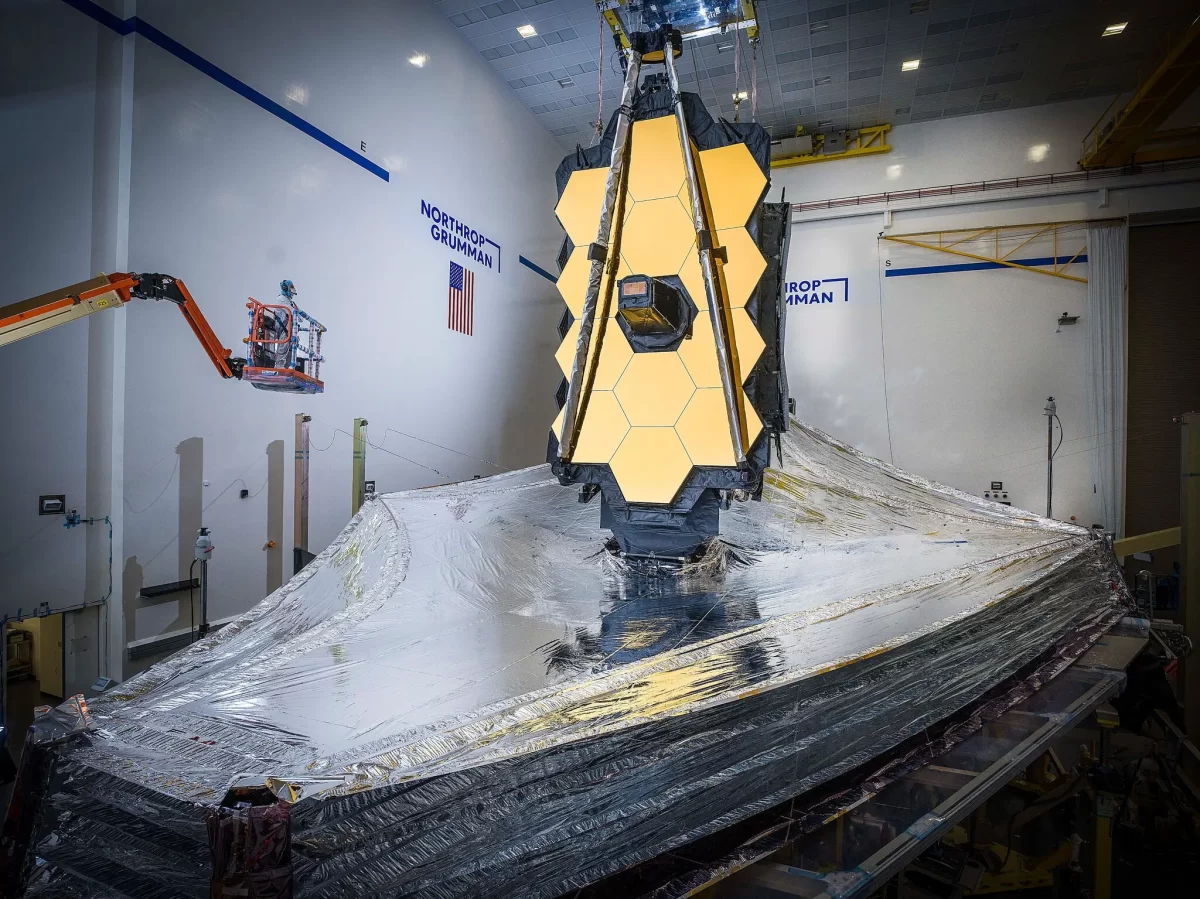

Final tests on the telescope’s sun shield at Northrop Grumman in California in 2020: Northrop Grumman

Just as the Hubble Space Telescope defined astronomy for the last three decades, NASA expects Webb to define the field for a new generation of researchers who have been eagerly awaiting their own rendezvous with the cosmos.

It’s been a long time coming. What began as the Next Generation Space Telescope evolved into an infrared telescope capable of sensing the heat from the earliest stars and galaxies in the universe.

Because the cosmos is still expanding, those earliest stars and galaxies are rushing away from Earth so fast that their light is shifted to longer, redder wavelengths, much as the sound from an ambulance’s siren shifts to a lower register as it speeds by. The light from the most distant and earliest galaxies and stars, once blue, is now infrared “heat” radiation, invisible to the eye. So too is the radiation from carbon, ozone and other molecules that are of keen interest to astrobiologists.

An early planning committee concluded that the telescope would need to be at least four meters in diameter (Hubble’s was just 2.4 meters across) and highly sensitive to infrared radiation, and it would cost $1 billion. NASA’s administrator, Dan Goldin, liked the idea but worried that a four-meter telescope would be too small to see the first stars, so he increased the size to eight meters.

Doubled in size, however, the telescope would no longer fit aboard any existing rocket. That meant the telescope’s mirror would have to be foldable, and it would have to unfurl itself in space. NASA eventually settled on a mirror 6.5 meters wide, with seven times the light-gathering power of Hubble’s.

Moreover, the telescope would have to be cooled to minus 380 degrees Fahrenheit to prevent the telescope’s own heat from swamping the faint emanations from distant stars. (One instrument had to be even colder, minus 447 degrees Fahrenheit, just a few degrees above absolute zero.) This was accomplished by parking the telescope permanently behind a sunshade.

But all the challenges of developing and building the instrument remained. In 1990, NASA had sent Hubble into orbit with a misshapen mirror; still stinging from that embarrassment, the agency devised a long and expensive testing program for the new telescope. The price tag rose to $8 billion, and in 2011, Congress nearly canceled the project.

“Webb became the perfect storm,” Dr. Dressler recalled. “The more expensive it got, the more critical it was that it not fail, and that made it even more expensive.”

During one early test, the sun shield was torn.

“When you work with a $10 billion telescope, there are no small problems,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for science missions. “It’s hard to know what’s boldface and what is not.”

The Webb telescope represents the combined effort of about 20,000 engineers, astronomers, technicians and bureaucrats, according to Bill Ochs, who has been the telescope’s project manager since 2011. It is now orbiting the sun at a spot called L2, where the combined gravitational fields of the sun and Earth create a stable resting spot. Its mirror, made of 18 gold-coated beryllium hexagons, suggests a sunflower floating on the blade of a giant shovel — the sunscreen that keeps the telescope cold and pointing ever outward from our star.

All of Webb’s troubles vanished on Christmas morning, when a flawless launch from French Guiana and lifted the telescope past hundreds of “single points of failure” and left it with twice as much maneuvering fuel as expected and the possibility of a 20-year career in science. The mirror also proved to be twice as good as expected at detecting the shortest wavelengths of light, increasing the telescope’s resolving power.

But will it have the power to reshape the views of millions of people on Earth, who still cling to a fairy tale of a planet created only 6,000 years ago by an unseen god up in the sky? Not as long as there is “fake news,” politicians and preachers willing to exploit it, and millions of people willingly hoodwinked by a bedtime story.

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal.

Ever since I learned several years ago about the audacious plans for James Webb I feared that the likelihood of failure was very high. What a miraculously flawless start to the mission. Just amazing, perhaps the greatest engineering achievement ever, and certainly something that *should* bring people together.

We are unfortunately still searching for that illusive story of science that will grab the attention of the world and eclipse the damn Bible. While millions of people are sharing the images on social media, very few actually have a clue what they mean.