The Big Picture –

By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Do you ever feel like you are marking time, waiting for something to happen? Something that is supposed to happen, but the timing is not yet right? I was thinking that recently when watching the movie “Field of Dreams.”

“The one constant through all the years has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time,” James Earl Jones says as Terence Mann in the film.

“This field, this game: it’s a part of our past, Ray,” he says to the Iowa farmer Ray Kinsella played by Kevin Costner, who is searching for something to heal his broken relationship with his late father John, a devoted baseball player and fan.

“If you build it, he will come.”

Ray fears growing old without achieving something, especially peace with his father. He never got to say goodbye.

“It reminds us of all that once was good, and what could be again.”

This field of dreams speaks to us all, but perhaps most presciently to those of us who played baseball as kids and dreamed of having a life in professional sports. It also speaks to me because I too lost my dad at a young, critical age.

But as you grow up and realize genetics has as much to do with it as practice, that you are not going to grow tall enough, fast enough or coordinated enough, you don’t go crying into the night.

Building a ball diamond for the ghosts of the giants of American baseball, like “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, is not for everybody. What do most of us do? We modify our dreams and move on in life.

When the idea first came up to write about this theme, it was a mid-career disappointment I had on my mind. Some things that happened 20 years ago. We’ll get around to that.

The more I thought about it, however, the more value there seemed to be in going back to the beginning. There may even be a book in it, or at least a new chapter in my memoir, Jump On The Bus: Make Democracy Work Again. At the very least there may be something therapeutic about it, and maybe not just for myself.

Sometimes narrative stories and information can help others to cope, especially in this stressed out warming world we live in today.

Fully realizing that I’m not alone in this, as Dr. King says in his sermon in Montgomery, this is “one of most persistent realities in human experience.”

“Very few people are privileged to live life with all of their dreams realized and all of their hopes fulfilled. Who here this morning has not had to face the agony of blasted hopes and shattered dreams?”

Part 1: On Unfulfilled Hopes, Shattered Dreams

The more I read and think about it, how people deal with disappointments in life may very well be one of the most significant determinants of human character, maybe even individual destiny.

How many millions of kids the world over grow up with dreams of making it in the Big Leagues of professional baseball, football, basketball, other sports, or winning a Gold medal in the Olympics? Too many to count.

As I’ve often said, in teaching and other conversations, no matter how much you want something and how many hours you spend practicing, everybody can’t make it to the NBA or the NFL. There are a limited number of slots on the discrete number of teams.

So when people tell you you can can do anything you want to do in life if you work hard enough, they are not exactly telling you the truth. Many have died with the ambition to be president of the United States. Precious few ever have the chance.

As far back as I can remember, like millions of other kids, baseball was my first dream to go unfulfilled. I was passionate about baseball when I was four and five years old in 1961, the year the New York Yankees defeated the Cincinnati Reds in five games in the World Series.

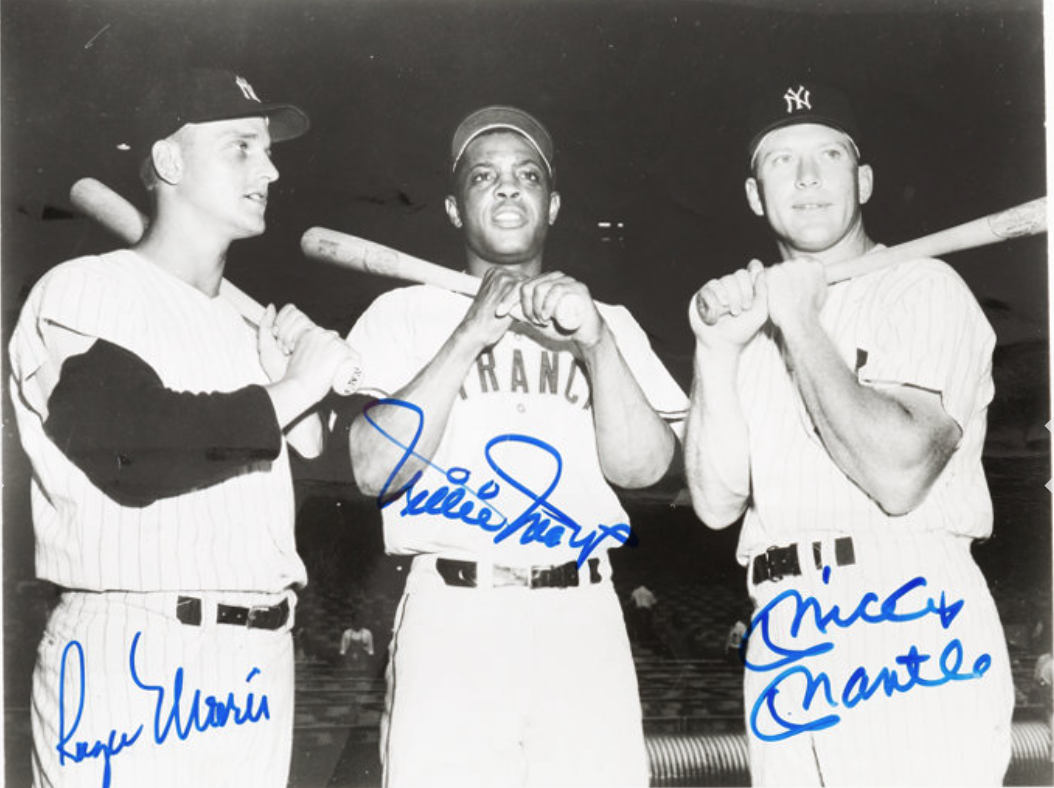

For anyone old enough to remember, or anyone interested in reading the history about it, the year was best known for Yankee teammates Roger Maris’ and Mickey Mantle’s pursuit of Babe Ruth’s renowned 34-year-old single-season home run record of 60. Maris ultimately broke the record when he hit his 61st home run on the final day of the regular season. He realized his dream, while Mantle was forced out of the lineup in late September due to a hip infection. He finished with 54 home runs.

Sorry Mick. But you had a great run, and did it with class. You will be remembered, along with Willie Mays with the San Francisco Giants then.

HBO made a film about it. On April 28, 2001 HBO’s film 61* premiered on television. Directed by Billy Crystal, starring Barry Pepper as Roger Maris and Thomas Jane as Mickey.

In the summer of 1962, they were my heroes. I was old enough to join a team in the Little League we had in the suburbs of Birmingham, Alabama. My dad was a big baseball fan, like John Kinsella.

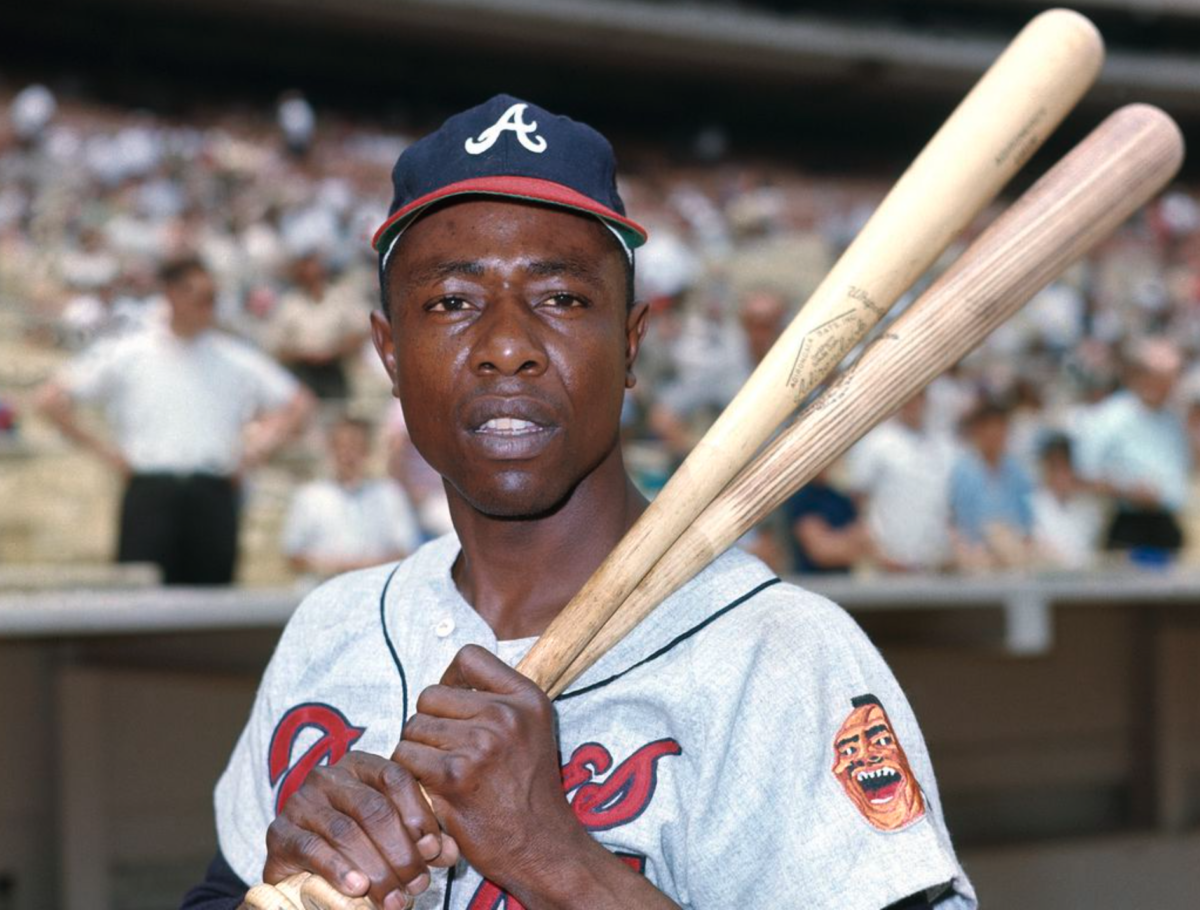

We following the Atlanta Braves. We often made the drive from Birmingham to Atlanta to attend games when Hank “the Hammer” Aaron from Mobile, Alabama was pursuing his career home run record. In the summertime, we would often stop by Six Flags Over Georgia along the way, mainly to ride the giant roller coaster, “The Great American Scream Machine.”

On April 8, 1974, with a record crowd of 53,775 in attendance in Atlanta, the game was broadcast nationally on NBC. In the fourth inning, Aaron hit home run number 715, topping Babe Ruth’s record of 714, off Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Al Downing. He would end his career in 1976 with 755 home runs. He got to live the dream and set many MLB records.

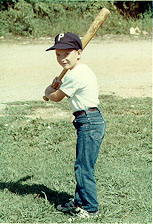

In 1962, my dad was friends with a coach of a team of kids in the first age level, so I got a blue baseball cap with a white P on it, for Peanuts. (I used to keep pictures of all the teams I played on over the next few years, but they all had to go when we sold the house in Birmingham in 2014. I did find this one).

I was so passionate about the game that for hours on many days I would toss a ball up against the bricks on our house to practice pitching and catching. It must have driven my mother crazy, but she never complained much. At least I was finding a way to entertain myself, and it was good exercise.

Not much about my Little League career is worth remembering or writing about, although I do fondly remember Saturdays in the park. Hot dogs with mustard, dill relish and sour kraut. Cokes back when they were made with real sugar. Giant balls of pink cotton candy. Bubble gum. The pretty girls, and big strong boys wearing cleats that clacked on the concrete sidewalks but dug in the dirt on the field. Sometimes you went home exhausted and feeling sick.

I remember one funny story from that first year.

For some reason, maybe because I was a little kid and no one had much confidence in my abilities yet, the coach stuck me out in center field. This was too far out for most of the five- and six-year-olds to hit the ball, so I didn’t get much fielding action.

But I remember my dad and the coach nicknamed “PeeWee” having a big laugh making fun of me for “dancing” around in the outfield. Since I wasn’t getting any action, I would pick up rocks and toss them up in the air and catch them. I wanted to play ball, and this is one thing you learn about the game of baseball — and life. Much of the time nothing happens. This can lead to boredom. I didn’t like being bored, so I found a way to entertain myself, by pretending I was playing baseball while playing baseball in the middle of a game.

Now that’s childhood. Or at least it was in the early 1960s in the suburbs before all hell broke loose.

Since I mentioned nicknames in the first dispatch in this series, I should mention that I would later earn the nickname “slugger” from one of my friend’s dads. Not so much for my success in Little League, but in the neighborhood games we played in back yards. I developed pretty good hand to eye coordination and could connect with the ball pretty well and place where I hit it, like up the middle over second base, in the gap between the third baseman and short stop, or over the second basemen’s head.

This would come in handy years later when I switched from baseball to softball. My Little League career passed without much in the way of glory, in part because of the politics of sports. Many of the coaches on teams I played on over the years would favor their own sons in the best positions in the field and the batting lineup, even if I could field and hit better. This was not only favoritism, it was nepotism. But that’s how it was, in a state that operated on a selfish, authoritarian style spoils system. I learned that there are selfish people in the world. Skill and merit did not always win out.

So in 1973, when I was about to signup for the Pony League, the final year of Little League, my mom talked me into switching to play for the new church softball team instead. My dad died in March of 1973 of a massive heart attack at the age of 47 after nearly 20 years of being worked to death by the telephone company, Southern Bell. Our church was the second biggest Baptist church in Alabama at the time, second in the size of the congregation to Dauphin Island Baptist Church in Mobile, and we had a burgeoning sports program.

It was so successful our junior high basketball team went undefeated for three straight years and won three state championships and a national championship. I loved basketball as well as baseball, but realized early on that I would never grow up to be seven feet tall.

In the summer after my ninth grade year, I joined the softball team and played short field, a position I mastered. I mopped up any line drives or grounders that made it out of the infield, and threw runners out at home plate with a perfect one bounce, something we practiced. I had the second best batting average on the team (.600), meaning I got a hit and got on base six out of every 10 at bats. The team did OK but we did not win a championship.

That would be the end of my youth sports career.

Faced with one of the first crucial decisions I had to make in life, I quit the high school football team in the fall and opted to play the drums in the high school marching band instead. It had to be done anyway. I could not very well do both. I had to give up on my first love in life, sports, and switch to my second, music. But I guarantee you that I had way more fun playing the drums in the band than my friends who stuck with football.

Our high school coaches were a bunch of unfulfilled assholes who had obviously failed in their life dreams of playing professional sports for a living. They ended up coaching high school teams instead, and seemed to take it out on their players. Two a day practices in August were a little like hell. We had one big, fat coach who played on the national championship team at Auburn in 1957. He spent the rest of his life torturing high school kids, sometimes with a big, fat paddle with holes drilled in it. I felt the sting of that paddle a couple of times, on the rare occasion I got caught skipping school. Mostly I didn’t get caught.

For the next few years music was the focus of my passion. Over time I put together a full drum set, a 1972 set of blue sparkle Ludwigs. I got a bass guitar one year for Christmas and a Fender amp. We had an upright piano in the basement that had belonged to my sister. I put together a PA system and invited other musicians over to my underground basement for band practice to play 1960s and ’70s rock and roll.

This also drove my single mother crazy, but she put up with it. I guess it was better to be doing it at home, not out somewhere else maybe getting into trouble. I sometimes worried about the volume we put out from the Fender and Marshall amps. Fortunately the neighbors never complained. You could barely hear the music outside. It really was an underground basement, built for the Red Scare era in the 1950s, when people started worrying about the threat of nuclear bombs from Russia.

We started out playing professionally for $75 a night in roller skating rings and private parties, and graduated to traveling to play big rock clubs all over the Southeast. I was playing clubs when I was only 16, and the legal drinking age was 18. I grew a funny beard and looked older, I guess. It was actually called a “cowboy” beard, an Abe Lincoln with no mustache. Too bad I don’t have more pictures from those days. I would later learn how to use a camera in college and take pictures.

I do still have this one, since I used it in the book.

The Orange Plus Band, with Mike Stewart on keyboards, Earl Waller and Chris Shepherd on guitars, Glynn Wilson on drums: Photo by Mike Stewart, who died of AIDS in Atlanta in the 1980s.

But I learned even more about human selfishness and ego, trying to be a musical entrepreneur. It seemed impossible to keep a band together. So I took the summer of 1979 off, and pursued another sport that would lead me to play on a college tennis team. As it turned out, they built a community college after clear cutting the forest I grew up playing in as a kid. That was a bit traumatic. But they built a library there, and that’s where I discovered my third love in life, English Literature and journalism. I also liked History and Political Science. I found out I got into politics.

This is a story I recently published revealing some things I learned at that time.

But I did get one more chance at sports. One of the guitar players I worked with in rock bands had a couple of tennis rackets, and there were courts all over the place in the neighborhood I grew up in. Some were even located near swimming pools. So every afternoon we would play tennis, then swim in the pool. At night we played rock music for a living, and often slept until noon. It was an interesting and fun life for awhile in the era of “drugs, sex and rock ‘n’ roll.”

I just couldn’t see a way to make a full living at it, in the absence of a coherent group of friends willing to put in the work and write original songs. I wrote lyrics, but everybody then just wanted to play copy music, get a paycheck, have some fun, maybe get laid. That’s what it was all about where I came from. Nobody was thinking about the art of it all.

This community college, I found out, had a world class tennis coach named Bal Moore. His teams won the state championship in the two-year college division like 21 out of 22 years. After playing tennis nearly every day for two years, I enrolled at Jeff. State. I took his tennis class like every quarter for two years, and got good enough to start practicing with the team in the afternoons. In my sophomore year, a spot opened up and I got to play on one of those state championship teams. It was the era of Jimmy Connors, Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe, so I had new sports heroes.

I could have pursued a tennis scholarship to a four year college, but by then I had fallen in love with writing news and taking pictures. I also figured out that I would never be big enough or good enough to make a living playing tennis. The prospect of working for newspapers seemed like a better life option. You didn’t have to be seven feet tall, and it turned out I was pretty good at it.

The successes and setbacks just kept on coming, like an army of steamrollers.

___

More in Part 3: On Unfulfilled Hopes, Shattered Dreams and Journalism.

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal. We just tell it like it is, no sensational clickbait or pretentious BS.

I remember meeting Emmett Ashford, MLBs first black major league umpire, he was a kind and knowledgeable man!