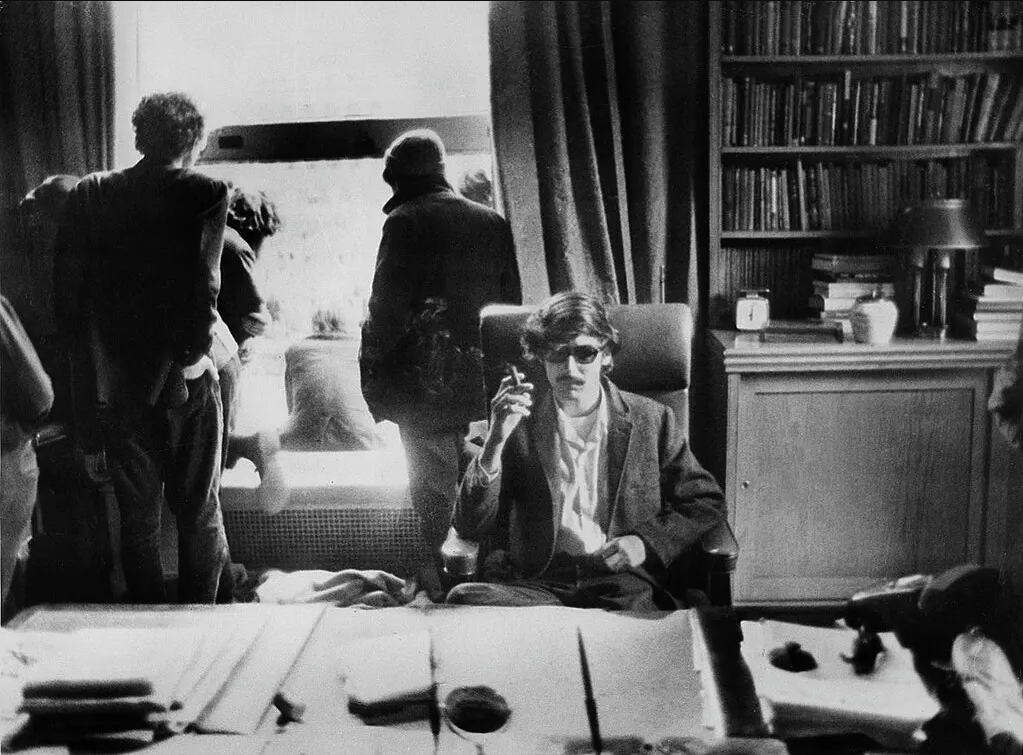

David Shapiro first tasted fame, albeit unwittingly, when he was photographed in the office of Columbia University’s president during the student uprising of 1968: NAJ screen shot

The Big Picture –

By Glynn Wilson –

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Since encountering the story early in my college career about Sherwood Anderson advising William Faulkner in New Orleans to write about people, places and things he knew something about, I’ve tried to follow that advice in my journalism career.

“Write what you know,” is the quote most often attributed to Anderson. But there was more to it than that. Anderson encouraged Faulkner to write about his personal experiences in his novels. He had been writing sketches for the Times-Picayune in New Orleans, but ultimately gave up on a career writing for newspapers and moved back to Mississippi to write fiction.

Admittedly, I don’t know much about the Middle East, and the ancient war between Israelis and Palestinians is a story I have gone out of my way to avoid. It’s too fraught a story it seems to me to accomplish much of anything by getting involved in it. If you criticize the Jews, you will be called an antisemite. If you criticize the Palestinians, you will be accused of Islamophobia. It seems to be a good example of when just telling both sides of a story is insufficient.

Then again, I’ve learned all kinds of things over the years about people, places and things I didn’t know much about – by taking on stories and learning while reporting and writing about them.

I do know something about protests in America, something I’ve covered on and off since the early days of the environmental movement and civil rights in the South.

So far when friends, fans and followers have asked me what I think about all the protests on college campuses related to the war in Gaza, my response has tended to lament why they are not protesting about global warming and trying to bring about societal change. I wonder why they are not protesting the criminality of Donald Trump, or the political corruption at the Supreme Court.

Let’s face it, there is much to protest about what’s going wrong in this crazy, mixed up world.

In the heat of the moment, you can’t control passion fired by outrage in the micro moment fueled by war, or necessarily steer people into focusing on what’s important for the future of American democracy on a macro level, or human survival on planet Earth for the long term.

It’s too bad, but you can’t.

Sometimes a story comes along that allows a writer to find a way to focus on something outside the normal sphere of expertise, maybe related to a story from the past that might have been incomplete and bring enlightenment to the table.

So here goes.

Background

Those who follow us closely know that we lost a critical friend, partner, editor and writer five years ago, the last time I traveled to Mobile, Alabama for the winter. When I arrived back in the Garden District, I found David Underhill weak from kidney dialysis and gave him a ride to the hospital. He died a few days later.

When I was working on his feature obituary, I found out some things about him I did not know. I knew he attended Harvard back in the 1960s, but did not know he also attended Columbia after that.

Mobile Writer and Activist David Underhill Dies at 78

After this story ran and was shared all over social media and showed up in search engines, I was contacted by a former best friend of Underhill’s, a Columbia Ph.D. graduate named Curtis “Corky” Seltzer. He found my story online and made the effort to get in touch. He told me about Underhill’s role in civil rights protests and opposition to the war in Vietnam at Columbia in the late ’60s.

That story was done, however, and I had to move on, ending up in Pensacola, Florida and then running from Covid. So I never went back and added much about that to the story. Just a mention of his attendance at Columbia. It seemed too involved and complicated and would be hard to check out and verify without Underhill’s input.

But this week, as I surveyed the news scene on the two big screens on my desktop, a story popped up that opened a window, creating an opportunity to explore this part of the story further.

David Shapiro, who the New York Times called “a cerebral yet deeply personal poet aligned with the so-called New York School, whose highly lyrical work balanced copious literary allusions with dreamlike imagery and intimate reflections drawn from family life,” died on Saturday in the Bronx. He was 77.

I did not know who Shapiro was, but according to the Times, Shapiro first tasted fame, “albeit unwittingly,” when he was photographed in the office of Columbia University’s president during the student uprising of 1968. The photograph (see above) ultimately ran in Life magazine and publications around the world. It became an enduring symbol of the student protests that roiled universities across the nation in the late 1960s.

Down in that story, there were links to other stories about what happened in 1968 related to the protests at Columbia and other universities now, so I started following the digital bread crumbs to see if there might be a story in it for me. I lobbed a call to Seltzer.

Related

Seltzer pointed me to a book and film by Paul Cronin called “Stir It Up,” based on the events at Columbia in 1968 and named after a quote from another Englishman, Thomas Paine.

“When the country, into which I had just set my foot, was set on fire about my ears, it was time to stir,” Paine wrote to inspire the American colonists to rise up and fight the British in the Revolutionary War. “It was time for every man to stir.”

You can see the film on Vimeo here.

Seltzer confirmed that Underhill was involved in the protests led by the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s. Some scholars consider it an example of the so-called “New Left” at the time in the U.S. That is discussed in this part of the film.

Underhill certainly considered himself to be a part of this. Even though the movement splintered and some say 1969 was the end of it, that did not stop activists from trying to resurrect it on and off over the next few decades.

Seltzer also told me some of the story of how Underhill’s involvement tainted his chances of graduating from Columbia, but ultimately led him to find his place in the world as a grassroots activist for civil rights and the environment in Mobile, Alabama.

For some reason, in all of our conversations over a friendship that spanned nearly 30 years, Underhill never told me about his involvement at Columbia. He often made jokes about the CIA, however, which I’ve also had some dealings with over the years.

Related: Havana Syndrome Clearly Caused by Directed Energy Weapon

SDS disdained permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships and parliamentary procedures, not unlike the Occupy movement from a few years ago and even Antifa. The founders conceived of the organization as a broad exercise in “participatory democracy.”

From its launch in 1960 it grew rapidly in the course of the tumultuous decade with over 300 campus chapters and 30,000 supporters recorded nationwide by its last national convention in 1969. The organization splintered at that convention amidst rivalry between factions seeking to impose national leadership and direction, and disputing “revolutionary” positions on, among other issues, the Vietnam War and Black Power.

According to Selter, who was Underhill’s roommate, Underhill was involved in writing a satirical version of a document called a “Festschrift” — a volume of writings by different authors presented as a tribute or memorial especially to a scholar — criticizing the university administration’s involvement with the RAND corporation and the Institute for Defense Analyses. It had been created in 1955 to foster the connection between Columbia University and the defense establishment. CIA and armed forces recruiters were known to visit Columbia to recruit students to join them.

The protests ultimately forced University President Grayson L. Kirk to retire before the next academic year after he was blamed for giving the order to call in police on campus to break up the protests, which resulted in cops beating up and injuring a number of students.

Seltzer contacted some of the other students from the time to see if a copy of this Festschrift could be found. If it surfaces and I can get more of the story, it may be worth a followup story.

After this story was first published, we heard from Linda Borus. Here is her recollection and contribution here.

“David was one of the most respected leaders of the grad/law school contingent of Columbia’s loosely organized SDS,” she wrote. “He and I (a fellow grad student) were more than ‘somewhat’ involved in the protests against the war in Vietnam, to the extent that we became ‘weekend warriors’, regularly attending any protests being held between NYC and our nation’s capital.

“Then came the spring of 1968. Turmoil on campus; organizing against the War more urgent.”

Their colleague, Prexy Nesbitt, was part of the Black students’ takeover of Hamilton Hall, Borus said.

“I recall David and I having a brief yelling to each other conversation with him as we stood outside HH and he in. That conversation spurred us into occupying the building that housed our Department as a way showing our support for the Black student’s list of demands.”

This is how Nesbitt characterized it, she said.

“Then at the Columbia thing in ’67 (’68), by that time I was already the editor of a citywide black student newspaper, and I was also one of the people, as I mentioned, busted. But I was one of the people pushing for the black students to link up with the white students as they took over buildings, because many of these students were graduate colleagues of mine. And I was also pushing for us to have a demand that would be not just around protesting Columbia’s expansion into Harlem with this gym but also to protest the war-related research that was being done at Columbia.”

“I argued those positions pretty much myself within the group that was occupying Hamilton Hall,” Borus said.

“Also, in that same interview, Nesbitt mentions Roger Hillsman’s efforts to recruit some of us, including David and I, a name Seltzer brought up (in the email).”

Here’s Nexbitt’s recollection:

“I was already talking to Shafrudin seriously and also had some exposure to a guy named Roger Hilsman who was teaching at Columbia,” he said. “I was in the course, I’ll never forget this. A guy named Davis Mugabe, a Zimbabwean, [and Borus] were in that course together.”

And Hilsman basically said to both of them, “I can create this great future for you guys doing work,” Nesbitt said.

“He was trying to recruit us,” he said (for the CIA). “This bastard was trying to recruit us.”

“And there were a bunch of SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] people in that same graduate seminar with me,” he added. “Linda Borus is one of them. I say that as these are all people who still are very active politically. And I think that just deepened my own commitment by that time to take some other options politically than anything that would be what Columbia could offer.”

Maybe that’s another reason Underhill left New York and found his way back to Mobile.

Story in Progress – More May be Added Here

Meanwhile, Seltzer sent me a copy of an op-ed he penned initially for The Washington Post, which was rejected by editors at the editorial page. Not being an expert on the region myself, it seems his thoughts and comments are about as reasonable as you are going to get in the coverage of this crisis. I always thought a two-state solution might be the answer. He argues for a one-state solution.

A One-State Solution Offers Hope

___

If you support truth in reporting with no paywall, and fearless writing with no popup ads or sponsored content, consider making a contribution today with GoFundMe or Patreon or PayPal.