There for the Birth of Southern Rock, he took the Muscle Shoals swampy sound to London and blended that with the Rasta island beat, creating a new sound that transformed Reggae for mainstream audiences in Europe and America. –

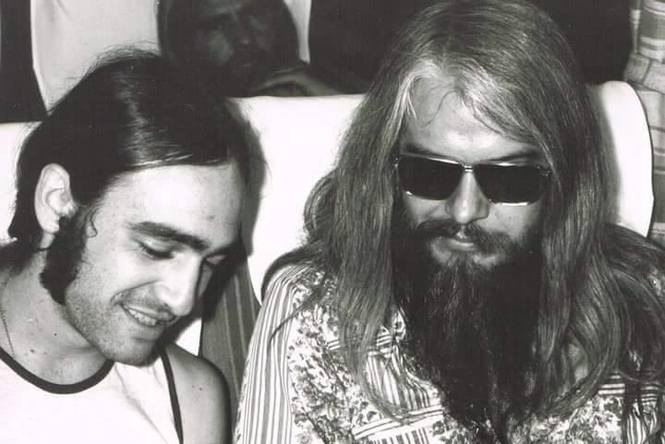

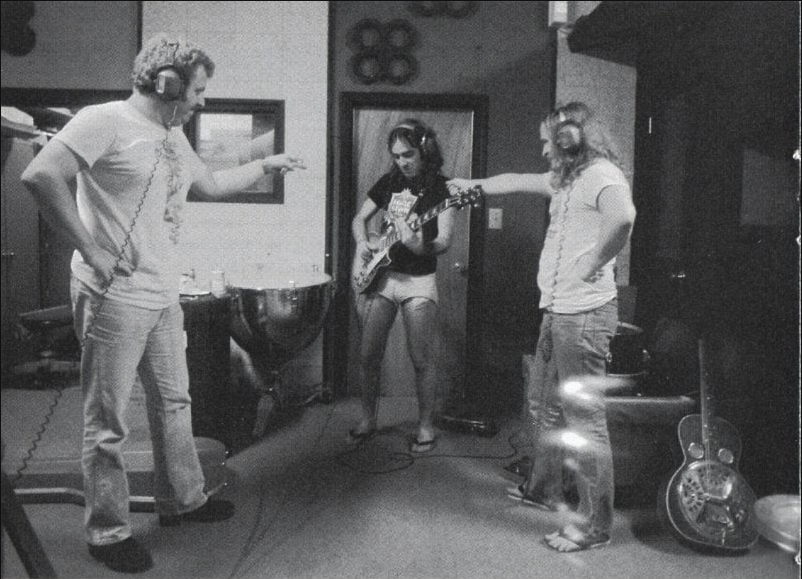

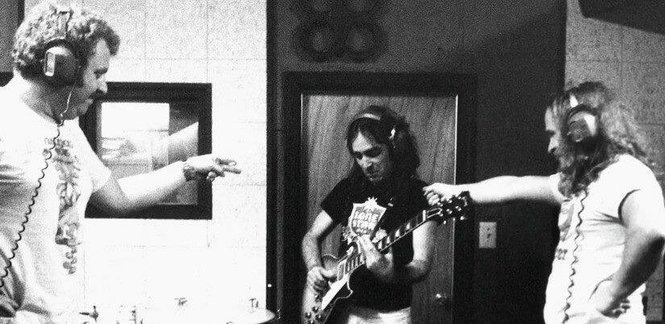

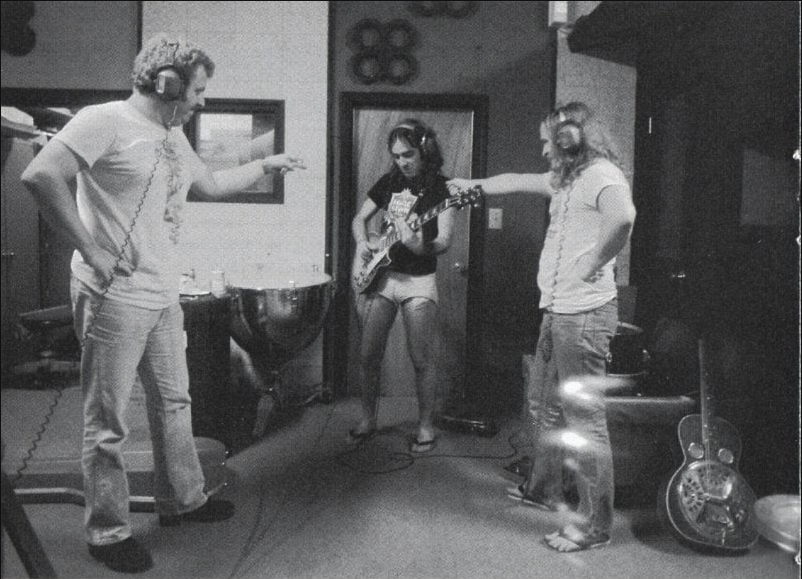

Legendary Swamper Jimmy Johnson (left) and Ronnie Van Zandt of Lynyrd Skynyrd (right) pointing at the man of the hour Wayne Perkins, come to save the day and session at Muscle Shoals Sound on guitar fresh from swimming in the Tennessee River: NAJ screen shot

A Draft Book Proposal in Progress

By Glynn “Cowboy” Wilson –

MUSCLE SHOALS, Ala. – (Jan. 26, 2025) – Guitar slinger, sideman and singer-songwriter Wayne Perkins of Birmingham, Alabama was only 18 in the revolutionary year of 1969, already playing bass and guitar in the studios of Muscle Shoals with hit generating acts like soul singer Percy Sledge, Wilson Pickett, Jimmy Cliff, the Staples Singers, on and on, when the Rolling Stones and Lynyrd Skynyrd came to town. Along the swampy banks of the Tennessee River in the remote, rural northwest corner of the state, far from the distraction of major cities, many of the world’s greatest musicians had already come from New York, Los Angeles and London to tap into the musical magic happening in the studios. It’s hard in retrospect to recreate in words what anyone was really thinking and feeling about all the Earth-shaking changes going on in the world at that time, except to the extent that they put their heart-felt personal feelings in their songs, like Joni Mitchell. Everywhere you looked, in the newspapers, magazines or on television news then, events seemed to be fulfilling the prophesy of folk rock guru and poet Bob Dylan when he first wrote and sang the song that Rolling Stone magazine would later declare as the Number One Song in Rock ‘n’ Roll history, “The Times They Are A-Changin’.”

It will take the skill of a writer who was there and lived through those times, knows the players intimately, studied historical research methods as a graduate student and college professor, and has spent the past 20 years experimenting with a new writing style partially based on the fast-paced, wide open prose of Hunter S. Thompson and Stanley Booth.

The most revolutionary event of the year came in July when the first human escaped the gravity of Earth and set foot on the Moon as 650 million people watched from all over the world. It was the largest television audience at the time, as Neil Armstrong took his first historic steps on the lunar surface after the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle landed – believe it, or not. Around the same time John Lennon and Yoko Ono got married at Gibraltar and staged a honeymoon “Bed-in” for peace in Amsterdam as the anti-war song “Give Peace a Chance” hit the radio airwaves and climbed the charts. President Richard Nixon and South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu met at Midway Island, announcing 25,000 U.S. troops would be withdrawn by September. Also in September, Lieutenant William Calley was charged with six counts of premeditated murder for the My Lai Massacre in 1968, resulting in the death of at least 109 Vietnamese civilians. In October the Days of Rage went down in Chicago and the Illinois National Guard was called in to control demonstrations involving the radical Weathermen in connection with the “Chicago Eight” trial. On orders from Charles Manson in August, members of the Manson Family invaded the Los Angeles home of film director Roman Polanski and murdered his pregnant wife, the actress Sharon Tate, and four others. A jury found Sirhan Sirhan guilty of assassinating of Robert F. Kennedy in April. The Santa Barbara oil spill began off the coast of California in January, inspiring Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson to organize the first Earth Day in 1970.

Then after 147 years of publishing, the last weekly issue of the Saturday Evening Post came out on newsstands in the United States, arguably the beginning of the end for print publications. The first electronic message was sent successfully between two computers connecting the University of California, Los Angeles and SRI International, a preview of the technology that would become the internet. It was the first whisper of a hint that change was coming for publishing. Newspapers actually had their heyday in the last half of the twentieth century, the big chain mass circulation daily newspapers rolling in twenty percent profits, way higher than oil at that time.

The Woodstock Festival was held in August near White Lake, New York, featuring some of the top rock stars of the era in a mud soaked rock-hippie love fest that would change how musicians performed and audiences interacted forever. At the age of 27 in July, Brian Jones, a British guitar player with the Rolling Stones, was found dead in the swimming pool at his home at Cotchford Farm in East Sussex. Tragically in December, Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death by Hells Angels at the Altamont Free Concert, which came to be viewed as the end of the hippie era and the de facto conclusion of late-1960s American youth culture movement – although that movement did not really end. It just migrated to the American South in the 1970s and shook up the culture in the Heart of Dixie. Read on, baby…

Way Down in Alabama

With all this wild stuff going on in the country and the world, one day by the Tennessee River down in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, the rhythm section players who would later come to be called The Swampers took a lunch break in town from Fame studios, leaving behind Wilson Pickett and Duane Allman. The locals didn’t cotton to Black people or Long Hairs in their public establishments. But the ’60s came to the South and Bama in the ’70s whether they liked it or not, along with Levi’s jeans, cowboy boots and wide belts, creating the new redneck hippie, as I’ve written in the past. They got together and played what Southern preachers started calling “the Devil’s music” with Black musicians, also hanging out with them not only in recording studios, but in hotels, bars, restaurants and swimming holes – and even in bed sometimes, Dog forbid.

Allman argued for covering the Beatles song because he saw an opportunity to play slide guitar leads and jam the song out, like those hits that became so popular later on Allman Brothers tours and records. The song was released as a single in 1968 on the band’s new Apple record label. It was a number one hit across the world, the year’s top-selling single in the UK and the U.S., Australia and Canada and remained Number One for nine weeks, a record it held for nine years, ultimately selling more than eight million copies. It’s frequently included on lists of the greatest songs of all time.

Duane was listening to all the new music coming out and munching back at the studio with Picket, then starts jamming on “Hey Jude,” putting in his own unique guitar leads and riffs. He suggested that Picket cover the hit song. Rick Hall was skeptical. But by the time the other players got back from lunch, the recording session schedule was scrapped. In an independent documentary on the Shoals music scene released in 2013, guitar player Jimmy Johnson leans in and looks right into the camera and utters these immortal words: “All of a sudden, there was Southern Rock.”

Look up the song on YouTube and listen as the track progresses from a straight cover version, then develops into a Southern Rock dance jam, with Pickett screaming his head off. For that bit of brilliance in the studio, we have Duane Allman to thank. That’s a well told story in certain circles, only it’s now reaching a new generation of musicians and music fans who may not know it yet. But wait, there’s more.

Southern Rock

Of course that was not the only place Southern Rock was being seeded, hatched and born. Ronnie Van Zandt had a band down in Jacksonville, Florida called Lynyrd Skynyrd that made a significant pass through the Shoals and eventually came away with hits that live on as any listener of classic rock radio stations can confirm. Just down the hill in Sheffield, Wayne Perkins was playing bass on Percy Sledge records in the Quinvy studio, they called it, cranking out hits exploding on the radio airwaves then, many picked up and distributed by Atlantic Records in New York. Sledge hit Number One on Billboard with “When a Man Loves A Woman” in 1966. It became the first Gold Record for Atlantic Records, so he was back in the studio again working for more with music journalist turned record producer Jerry Wexler. He went from writing for Billboard to producing the hits that would dominate the charts for years. According to Wayne and other local sources, including Dick Cooper, “he always seemed to be around,” scouting for talent and looking for hits.

Slide guitar techniques often came up with players in between sessions, and Duane’s use of a glass cold and pain pill bottle became a fascination that lives on even today. He got motivated after listening to a Taj Mahal record Gregg gave him to listen to after he fell off a horse and injured his elbow and couldn’t play for six weeks, right before he was planning his move from California to Muscle Shoals. At the same time Perkins, being raised around tools and helping his dad Milford fix up cars, adopted a Craftsman nine-sixteenth, long-weld socket as a slide. Blues players then and rockers now prefer a metal slide. If you drop a glass and it breaks, the thinking goes, what then? Allman wore his glass on his left ring finger. Perkins always wore his on his little pinkie, he told me, “to keep one more finger free for chords.”

The musical gumbo was being cooked up by musicians in what was the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section who came to be called The Swampers, for laying down a certain rock groove with a Southern blues feel that seemed to ooze out of the swamps and onto dry land under the cover of moonlight, inspired by the spirit singing in the river, a Cherokee legend. The world beat a path to their door, and wealth and fame followed for so many. The nickname “The Swampers” was coined by producer Denny Cordell during recording sessions for Leon Russell because of their “funky, soulful Southern ‘swamp’ sound,” according to one popular version of the story.

Related: What is This ‘Swampers Sound’ and What Musicians Should be Credited on the List as ‘A Swamper?’

Video Interviews with Wayne Perkins and Stephen Foster

Wayne Perkins was there in the studio, playing with Leon Russell, and he recalls Russell using the term to refer to the studio musicians as the support staff for the stars. The term has dual meanings, and being from Oklahoma, Russell must have known it also referred to the support staff for cowboys on cattle drives. When I asked Perkins about this for a video reel in late 2024 at his home in Argo, he said, it was about the studio musicians cooking up the music “like the cooks on a cattle drive.” It may inspire controversy, but Wayne considers himself one of the original swampers, along with Spooner Oldham on keyboards, even though they are rarely given credit for that. Perkins was there mostly playing lead guitar parts, while the other band members played on hundreds of records on rhythm guitar, bass guitar, keyboards and drums. Jimmy Johnson was the main rhythm guitar player, with David Hood on bass, Barry Becket on keyboards and Roger Hawkins on drums.

In January 2025, when running into Paul Wexler, Jerry’s son, who flew in from California for Dick Cooper’s 79th birthday party at the Alabama Music Hall of Fame Museum, the question on the mind was his take on what that “swampers sound” meant to him, his first thought. “It’s all about the drummer,” he said, looking right into the camera. “Roger (Hawkins) is the one who created that swampy vibe the most.”

When Wayne heard that as I played it for him over the phone to get his reaction, he laughed his little laugh, and said: “He’s right.”

But it was more than that, that sound on guitar Chris Blackwell heard in the Shoals from the guitar of Wayne Perkins, after Duane Allman was gone, along with Eddie Hinton. Blackwell signed him to a record deal with Island Records and took him to London. (In the video, I use Perkins’ lead in to “Just Dropped In,” I think the best cover of the song ever).

Perkins had arrived in Muscle Shoals in early 1968 after a fight with his dad about his long hair, he told me, and probably because he wanted to quit school – knowing he wanted to play music for a living. He hightailed it to “Muscle Shoals” and landed at Quin Ivy’s studio in Sheffield, getting hired as a session player for $100 a week on the recommendation of drummer Jasper Guarino. Because of the address of the Perkins family house on 25th Avenue in East Jefferson County, he had attended both Hewitt High School in Trussville, then Erwin High School in Center Point, as well as the vocational school at Tarrant. Like many of us creative types back in those days, he found school mostly boring, he confirmed with me. The classes and teachers didn’t hold his attention and, because of his outspoken nature and yes, long hair, he was not in good with the local administrative establishment, a.k.a. “the Man.” Many of us at the time could relate. Alice Cooper expressed it best with his hit single in the spring of 1972, “School’s Out” … “for summer.”

“School’s out for summer

“School’s out forever

“I’m bored to pieces…”

About the time he turned 18, Perkins was hanging out with Eddie Hinton by a tree near the studio (there is a famous picture of them together online). Hinton was a talented guitar player and singer-songwriter, but a crazy kid who did not handle drugs and alcohol well. Johnny Wyker of the band Sailcat, which had one hit with the song “Motorcycle Mama” that made it to Number 12 on the Billboard charts and was featured on an episode of “American Bandstand” with Dick Clark, was a close friend of Hinton’s. While working for a newspaper in Decatur in 1985-86, Wyker told me a story about Hinton screaming at the top of his lungs in the bathroom before a session to try and scar his vocal chords and achieve a raspy sound in his voice like Joe Cocker, an artist Perkins would later play with in the era of Mad Dogs and Englishmen with Leon Russell. Perkins confirmed the story in an interview while working on this book.

According to an interview with Perkins in the mid-1990s, Wayne recalled, “Eddie told me, ‘I’m leaving here. You want this gig? Duane’s gone and he ain’t coming back. He’s busy’.” Duane Allman had started out playing at Rick Hall’s Fame studio. But when the core band nicknamed the Fame Gang Two walked out in a pay dispute and opened their own studio on Jackson Highway, Allman went with them for a short time before moving to Macon, Georgia and forming his own band with his brother Gregg.

Perkins has often told his story about the “job interview” at Muscle Shoals Sound.

“I went in to talk to Jimmy Johnson. He handed me a stack of records about two feet tall, and it’s albums of all these different players, all the greatest guitar players,” Perkins says. “Johnson said, ‘I tell you what. You want this job? You want to be one of us? I don’t want to be sitting in the control room with [Atlantic Records executives] Ahmet Ertegun or Jerry Wexler and ask you to give me a little something more like a Cornell Dupree lick or a little more ‘Duane Allman kind of blues’ style, and you not be able to do so. Any kind of guitar lick I ask you for, I don’t want to see any kind of doubt on your face. You just nod your head and go on with it. Don’t embarrass me in front of Ahmet or Wexler because these guys are our bread and butter.’ So I went home and took about two weeks and consumed that stack of records. And I got the gig.”

At 15, still in school, Perkins actually got his first gig as a session musician at Bob Grove’s Prestige Recording Studio on First Avenue in Birmingham. He performed live with a couple of local bands from Birmingham, including the Colours and the Vikings. Charlie Nettles, a fellow band member, recalls that Wayne left home at 16 to live with him and his mother after the fight with his dad and quitting school. Recognizing his natural talent, drummer Jasper Guarino encouraged him to leave the band to join him in the Shoals at Quinvy as a session player.

“That was the start of my professional career as a studio musician, going to work for Quin Ivy,” Perkins says. “He had a rhythm section funded by Atlantic Records to record Percy Sledge and a couple of other artists. It was something I loved and one day Jerry Wexler walked into the control room. I remember Quin saying that Jerry WAS Atlantic Records and that we were supposed to make him happy with our work. So you can imagine this young upstart from Birmingham was quite beside himself. Well, the gig lasted for about nine months and then there was no more funding. So the band had to decide what to do because Quin couldn’t afford to keep us on. So everyone went their separate ways, except for me… I didn’t want to leave.”

“So Quin Ivy took me aside and said, ‘Listen, I’ll pay your rent and one meal a day, and maybe after a while you can get some demos or something up on the hill’ (at Muscle Shoals Sound). Quin was right – I started getting work there, at first with people like David Porter and the Soul Children, Dave Crawford and Brad Shapiro, and Dee Dee Warwick.”

Chris Blackwell of Island Records heard about the musical magic happening in the Shoals and started bringing some of his artists to record at Muscle Shoals Sound, including Jimmy Cliff from Jamaica. Blackwell was impressed with Perkins, and had him team up with the Smith brothers as lead guitar player and singer and formed his first American band, Smith Perkins Smith. After Blackwell funded their trip to London and released their one and only record, they toured Europe opening with Jackson Browne for the headline act, the band Free, which had a hit on the radio at the time, “All Right Now.”

Blackwell had Perkins team up with the Smith brothers to put together a showcase of songs. When he heard them play, he said, “Y’all have a record deal,” as Perkins tells the story. “Do you want to break from here or London?”

“We looked at each other and back at Blackwell, and said, ‘what do you think?'” They flew to London.

Wayne says he didn’t realize Blackwell intended to use him on sessions with other artists at Island Records in London, but this was all right by him.

“I ended up playing on a bunch of people’s records,” Perkins says. “Walking around England with a guitar in your hand doing session work is a good way to be discovered.”

At 73 his memory is hazy, but when prompted he remembers turning 21 in London, so that places him there in September, 1972, for sure. Putting together a definitive timeline on his life and career has not been easy, since as his brother Dale says, “He was always coming and going to and from somewhere, Muscle Shoals or Tulsa, LA or London.” He was born on September 6, 1951. Their mom Earline could remember all those times when Wayne needed a ride to the airport, or a ride home, and when and where he came and went from, Dale says. He was often busy working in bands himself and not always around. But he recalls it as a whirlwind of activity.

“At the time we didn’t think that much of it,” Dale said in an interview in 2025. The family fully expected Wayne to become a major rock star, since he was such a natural talent from a very early age. And of course he possessed a certain charisma, as I discovered in the spring of 1975 when first meeting him on the front porch of that shotgun house the family lived in, and that Fourth of July Skynyrd concert that summer at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, when I gave him a ride and watched him play “Sweet Home Alabama” with the band in an encore to a show that ended with the Birmingham police pulling the power plug.

It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll But I Like It: Wayne Perkins, The Rolling Stones and Lynyrd Skynyrd

At Basing Street Studios in the basement of Island’s London offices, Blackwell was trying to figure out what to do with a rasta band from his native Jamaica then called The Wailers. Knowing Perkins’ reputation for being able to come up with guitar riffs, fills and leads on records in the Shoals, he asked Perkins to sit in to see what he could come up with for Bob Marley. Perkins says when Blackwell “tossed me in the mix with this reggae stuff, I didn’t know what it was.” At first, Pickens struggled to find the groove on this new fangled music. Blackwell tells the story in his book and a documentary about having the sound engineer turn down the bass guitar track on “Concrete Jungle,” since it was more of a lead line in the Reggae songs, and a distraction in a way.

“I’d never played on anything like that,” Perkins says. “But I’d been thrown in the mix with a lot of heavy duty bluegrass players so you couldn’t really scare me with anything.”

Perkins finally found the groove, and recorded some guitar parts, including a lead using a wah-wah peddle with an echo effect. Marley was listening and watching in the control room. When it was done, as Perkins tells the story, Bob “ran out there with a spliff about two feet long trying to cram it down my throat,” he says. Wayne went on to overdub a smoky slide solo on “Baby We’ve Got a Date” and slow-motion wah-wah for the sexy ballad “Stir It Up.” Perkins says he was not credited on “Catch a Fire” until a 2001 reissue, but it didn’t bother him at the time.

“It just showed me what the industry was about,” he says. “When I booked that I didn’t really put everything under a magnifying glass.”

Like freelance writers who often get paid by the hour under the Fair Labor Standards Act, studio musicians were often in the same boat, working for hourly or weekly wages, or paid by the session. While Bob Marley’s records went on to international fame and became gold records, making millionaires of the core band members, Perkins did not end up rich from playing music, or household-name famous. But to in-the-know musicians and music fans, especially from Alabama, he’s considered one of the great guitar slingers of the early rock and roll era, and one of the most significant talents to come out of Alabama in those days, with a voice to die for. Range and howl.

“I’ve made some money off of it, but it wasn’t like I was a band member,” he says. “Those guys make some money and that’s the thing you learn as you get into these deals. But as a session player you can’t get attached to that kind of thing.”

So it wasn’t all about the money. It was the art, the creativity, with the best, in prime time.

In Island Records legend Chris Blackwell’s book The Islander: My Life in the Music Business and Beyond, he tells the story this way.

In 1972, Jamaican singer Jimmy Cliff got tired of waiting on commercial success at Island Records and walked out on Blackwell, signing with Reprise Records, the record label started by Frank Sinatra that became a subsidiary of Warner Brothers. Right after that, Bob Marley and the band The Wailers were in Europe looking for a record deal. They met Blackwell in London and he gave them four thousand pounds to help them make it back to Jamaica to write songs for a record – with no written contract. The staff thought he was crazy, but he liked their force and confidence and sensed they felt screwed over, so he decided to trust them. It paid off big. Blackwell had taken Cliff to record in Muscle Shoals and met Perkins and heard him play. He was impressed.

“Having a different kind of guitar – a rock guitar with lean, Southern-blues flaver – changed everything,” Backwell says. “How this guitar ended up on ‘Concrete Jungle’ was a happy accident … A white American guitarist named Wayne Perkins happened to be working in the Island studios. He was part of the crack sessions team at the Muscle Shoals studio in Alabama that had backed Jimmy Cliff while I had been there. He had also played behind such legends as Wilson Pickett, the Staples Singers, etc. So impressed was I by the Muscle Shoals guys that I plucked three of them, Wayne and the brothers Steve and Tim Smith. (Steve Smith would go on to become a producer at Island, including Robert Palmer’s first two solo albums, the first being Sneaking Sally Through the Alley).

One day while going up the spiral staircase in the studio offices, Blackwell ran into Perkins coming down the stairs, and asked if he would sit in on the Marley sessions on guitar. “He was the kind of musician who offered a quick ‘Of course!’ when you asked,” Blackwell writes.

“Wayne had no experience playing Reggae and had barely heard any. He was more of a Duane Allman type, virtuosic and chivalrous. He nearly joined Lynyrd Skynyrd and, a little while later, was on a short list to replace Mick Taylor in The Rolling Stones, losing out to Ronnie Wood, mainly because he was not English. I told Wayne not to let the word Reggae get in the way, to just play what he felt. He met Bob briefly, there was a lot of smoke wafting through the studio, and when he started playing ‘Concrete Jungle,’ he started from nowhere, literally and figuratively in a kind of fog.

“When the track began, you could tell he didn’t know where he was in the music. He was lost. He said it sounded to him like the music was playing backwards – it seemed simple and spare but had so much nuance and complexity, so much dynamism in what seemed to be empty space. He was distracted by the bass, which sounded like it was playing lead. I told him to ignore it. To help, I got the engineer to turn it down (the bass track).

“Wayne started messing about, then eventually locked into something, the way the keyboards and rhythm guitar grooved together all the way through the song. He held on tight and brought in that roots, dirty, swampy Muscle Shoals. The fog cleared.

“Bob, who had been listening intently (in the control room), was thrilled. He was so excited he jumped all over Wayne, patting him on the back, stuffing a huge joint into his mouth. Wayne got pretty damned high that night – he had become a white Wailer. As for Bob, he immediately knew something important had happened: a launch in a new direction, a mysterious melding of time and place, the American South and Jamaican swagger, that somehow made sense.

“‘Concrete Jungle’ became the first track on the record, so that guitar – which for ages people assumed was Peter Tosh rather than a white guy from Alabama, which was probably just as well – was how this new sound, these new Wailers, were introduced to the world. And it was the sound of someone learning about the music he was inside of at the same moment he understood it made it so compelling. Later, Wayne added some lovely hazy wah-wah to ‘Stir It Up’ and a sultry slide part to ‘Baby We’ve Got A Date’.”

“I love the way such connections are made, little nudges from the universe – I came across Wayne in a small town in Alabama because I was there chasing a certain sound for some of my artists, brought him over to England, bumped into him in the Island studios in Notting Hill because he happened to be recording on that day we were mixing. The second Smith Perkins Smith album, Wayne’s reason for being there in the first place, never got finished in the end. Doors open and close all the time. Sometimes you go through a door and find yourself in the right place at the right time.”

Blackwell also got John “Rabbit” Bundrick involved on the organ and clavinet, sounds which Stevie Wonder was pioneering on “Superstition,” and the rest is history.

Party Time

After hanging out in London partying with Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, even some members of The Beatles and other great musicians from the early days of British rock, Clapton had the idea to go to Barbados to take a break and “dry out” from all the hard drugs, the cocaine and heroine. Perkins followed him there, along with a couple of groupies, one who would later publish a tell all book about Clapton, the muse for the song Layla (we’ll get into the details in the book). But after a few weeks of smoking ganja and drinking rum, and after blowing the $13,000 he had made from touring and studio work in Europe, Wayne called his brother Dale in Birmingham and got him to wire $200 so he could fly back home to Birmingham. This was an early indication that as talented as he was as a musician, his inattention to detail as a manager of his own affairs was a weakness. At various times he had agents and managers and got by, but deep down there was a lack of trust. Although he tells great stories about his attorney Mickey Shapiro in LA, who helped get him out of the Vietnam draft in the early Muscle Shoals days (we tell the whole story in the book). Another time Perkins tells the story of hanging out in Jamaica with The Wailers. The Rastas smoked weed all day and night until they finally slept a peaceful island sleep to the sound of the Caribbean waves, their buzz enhanced by the island rum. He remembers political unrest breaking out on the island, so he got out of there fast and flew home. Marley was injured in a shooting when someone broke into Blackwell’s Kingston estate, where Marley was staying, and shot him in the arm. Even the C.I.A. kept a file on Marley for his potential influence on the radical youth. Blackwell confirms this story in his book.

After flying back to Birmingham and resting up for awhile in his childhood home, Perkins left again to play with Leon Russell and Joe Cocker on the Mad Dogs and Englishmen record and tour, and when Russell later hired the Gap Band and practiced in the Church Studio in Tulsa. Dale spent months there himself helping out as a roadie of sorts. There are a few videos on YouTube from those times. In this rare footage you can see Wayne Perkins playing a black Les Paul with hair down to his ass.

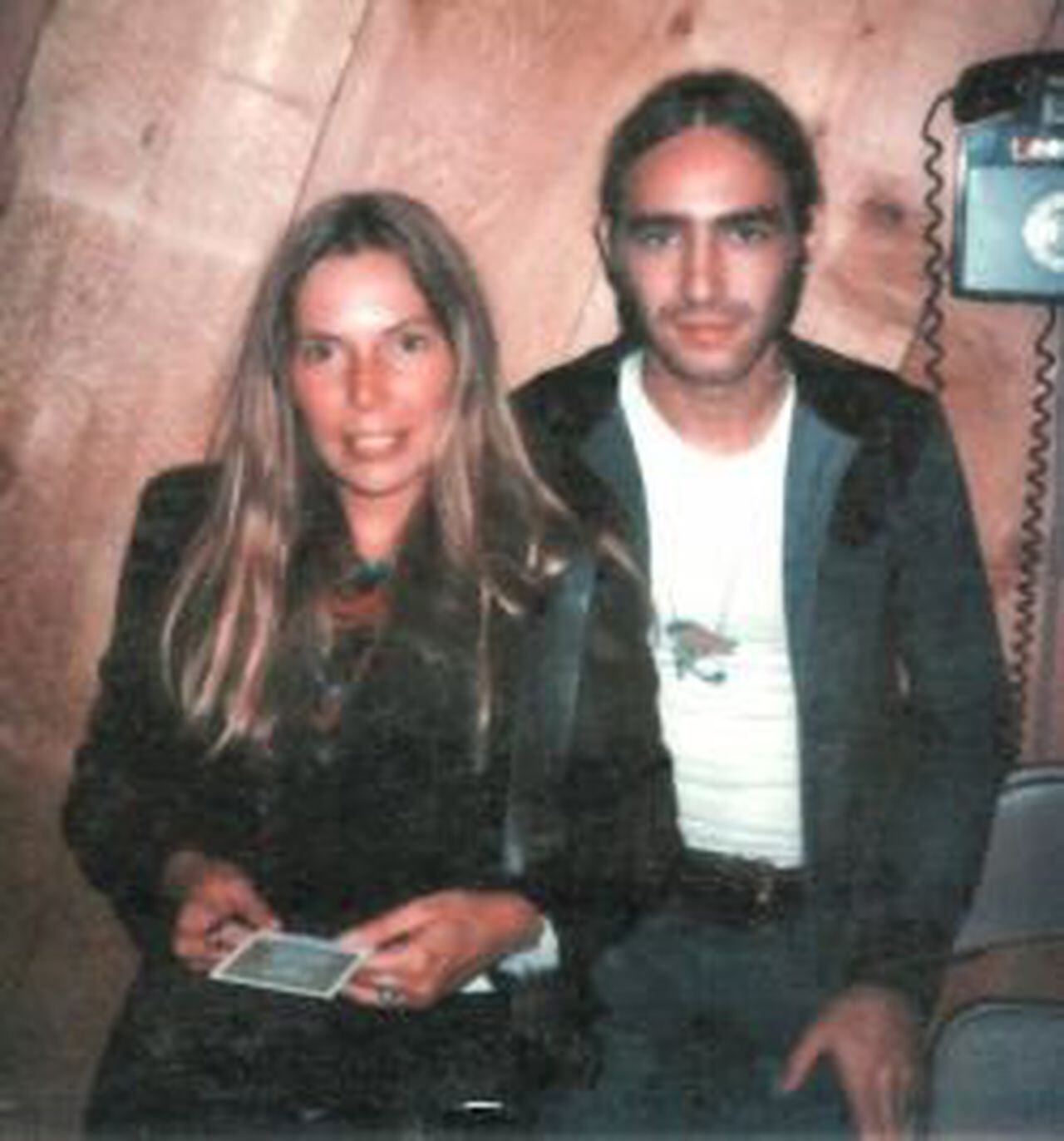

On a tour and recording break, Perkins talked to Jackson Browne, who encouraged Wayne to come out to California where he had signed with David Geffen’s Asylum Records. When he got there, Perkins found himself at the right place, right time again hanging out at Geffen’s Beverly Hills mansion with the likes of Jackson Browne, Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell. One day Joni came upstairs and woke him up, urging him to come downstairs to meet someone. She made him an omelet, Perkins recalls, as Bob Dylan sat at the table reading The New York Times. Joni got Wayne’s acoustic guitar and hers and asked him to play along. Dylan closed the paper, put it under his arm, Perkins says, and came over to listen.

“I offered him the guitar,” Perkins says, maybe a little star struck at playing for the folk guru and rock poet. Bob sluffed it off. “He said nah, your doing fine,” Wayne says, and picked up a tamborine and started playing along, keeping up the beat. “Here I was playing with the Tambourine Man himself. What a trip.”

At one point she came into his room and started hanging out. They made love, he says, and then he ended up in the Asylum studio in LA and laid down guitar tracks on the song “Car on a Hill” for the Court and Spark album, which came out in January, 1974. It’s arguably one of the most artistic records of all time. Even David Crosby admits this in interviews late in his life, in spite of the fact that Joni broke up with him publicly with a song, “That Song About The Midway.” The song “Car on a Hill” was allegedly about her being stood up by Jackson Browne one night. Apparently she was really in love with him, and once staged a suicide attempt and had to be rescued by Geffen, according to multiple sources. During this time in music history, the airwaves jumped with all manner of revenge songs from the failed love affairs of artists like Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham, Carly Simon and James Taylor, and others.

More to Come

There will be a chapter on Lynyrd Skynyrd, and why Perkins never joined the band before the plane crash in 1977, and related stories from those times. There will be a chapter on the Rolling Stones, and why he was not picked to join the band, with stories from those times. There will be another chapter on the Alabama Power Band-Crimson Tide period, including the shenanigans at Capitol that caused the failure of the band. And then we will deal with Wayne’s life and career after that, when he ended up in California writing songs with Richard Wolf, and playing out with Flying-V blues-rock guitar legend Lonnie Mack. Another chapter will deal with when and why Perkins came back home to Alabama for good, when his dad got Alzheimers in the 1990s, and he faced health problems of his own.

(When the book is done, we will provide all the photos and links to confirm all these stories for the online Kindle version of the book).

Arthur’s Note

Glynn “Cowboy” Wilson was only 13 in 1969 growing up not far from the Perkins house, and got to know Wayne, Dale and the Perkins family as a teenager while pursuing his own dream of playing the drums in rock bands. He would go on to play the drums in several bands and learn live sound engineering techniques himself, also managing and booking bands and other aspects of the business. But when he got frustrated with the music business and went on parole from rock and roll in the summer of 1979, he followed a new dream to become a writer starting out with newspaper and then magazine journalism, then become an early pioneer of web publishing. As a long time musician who came of age in the 1970s in Birmingham, he was an eye witness to many of these events. He would later earn a master’s degree and work on a Ph.D. in communications, learning the methods of historical research. That makes him the obvious choice to write the story of the life and times of Wayne Perkins. This is just the beginning of a sample chapter for publishers to consider funding this book and music history project.

In November 2024 after spending the better part of ten years in and around Washington, D.C. covering national politics, science and the environment, Wilson traveled back to his home state and city for a documentary film premier on the life and times of Wayne Perkins. Burned out on politics, and encouraged by Wayne and Dale to work on a book, Wilson ended up embedded in the newer Perkins house in Argo, east of Birmingham, in December 2024 and January 2025. He started a Wayne Perkins Music Legacy Project by building him a new website. His old one had disappeared back in 2016 when his long time agent Rudy Johnson died. Wilson also created a new Facebook Fan group for Perkins. He also redesigned a mostly dormant YouTube channel and began archiving Wayne’s song library so a new audience could find his work online. Much of it includes demo tapes that were mailed to the Library of Congress for the purposes of copyrighting the songs, but they mostly sit dormant in boxes in a storage unit and have never been heard by anybody, anywhere. We now have most of those songs saved as MP3 audio files and are in the process of publishing them as YouTube videos so that a new audience may find him. Perhaps other musicians might find them and cover some, potentially providing Perkins with the royalties he needs for a retirement fund. We also created a GoFundMe page to raise some of the expense money it will take to complete the website and YouTube channel, and to conduct research into the copyright status of all of Wayne’s original songs.

Wilson also started conducting research and interviews to piece together a definitive timeline of Perkins’ career, including a comprehensive discography. And Dale and Wayne both wanted a book to come out of this project, so this has begun. But it will take at least a year of work to write a full book, and this must be funded somehow.

When Wilson first found out about the film project in February, 2024, he took a week while camping in a national park campground in Maryland, just north of the D.C. line, and began tinkering with a story from those early days of rock and roll, and his part in it along with Wayne and Dale Perkins. What emerged was a new style of writing for him, inspired in part by the work of Hunter S. Thompson and Stanley Booth.

It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll But I Like It: Wayne Perkins, The Rolling Stones and Lynyrd Skynyrd

This could inform the style of a work on the life and times of Wayne Perkins. It is much easier for a writer to put himself in the story and write in the first person, present tense, to emulate the style Thompson and Booth pioneered in the late 1960s and early ’70s. But I have been toying with an idea of how to put the reader in the story with Wayne Perkins and create a fast read even today’s social media addicted youth with short attention spans might be able to consume. The online Kindle version of the book could be an innovative, interactive book with oral history interviews in video format.

(When my friend and former colleague at The New York Times Rick Bragg, also form Alabama, wrote his biography of Jerry Lee Lewis, a masterful work, he had the benefit of the extensive records Lewis had kept on himself over the decades, and Lewis was able in many ways to tell his own story. We will not have that luxury with Perkins, so this will not be a ghost written book “as told by” the subject. It will require extensive research, interviews with as many of the players important to the story as it is possible to find and talk to. We will conduct video interviews with as many people as possible, so this could also serve as an oral history project, and provide clips for a film).

Get in touch if you want to be the first to offer us a book deal to finish researching, writing, editing and to publish this work.

Photos

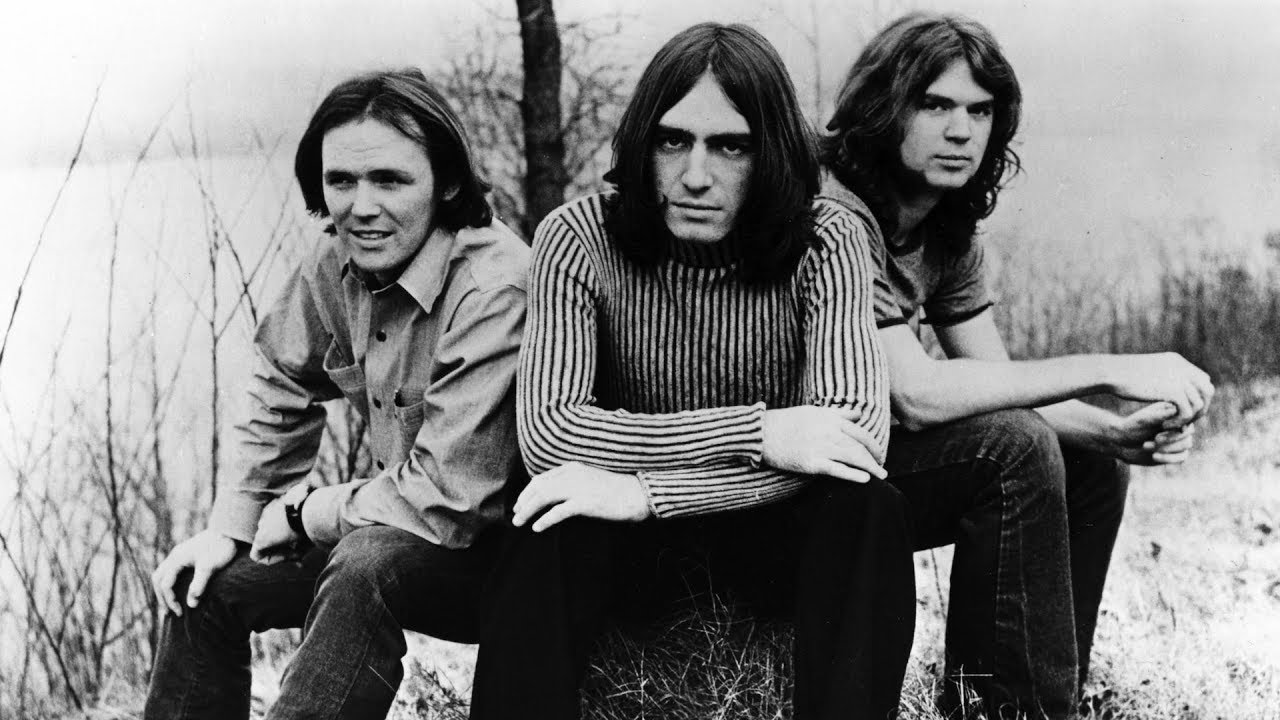

Wayne Perkins (center) playing guitar with Lynyrd Skynyrd as Ronnie Van Zandt (right) points at Wayne in the Muscle Shoals Sound studio. That’s Jimmy Johnson (left): NAJ screen shot

Legendary Swamper Jimmy Johnson (left) and Ronnie Van Zandt of Lynyrd Skynyrd (right) pointing at the man of the hour Wayne Perkins, come to save the day and session at Muscle Shoals Sound on guitar fresh from swimming in the Tennessee River: NAJ screen shot

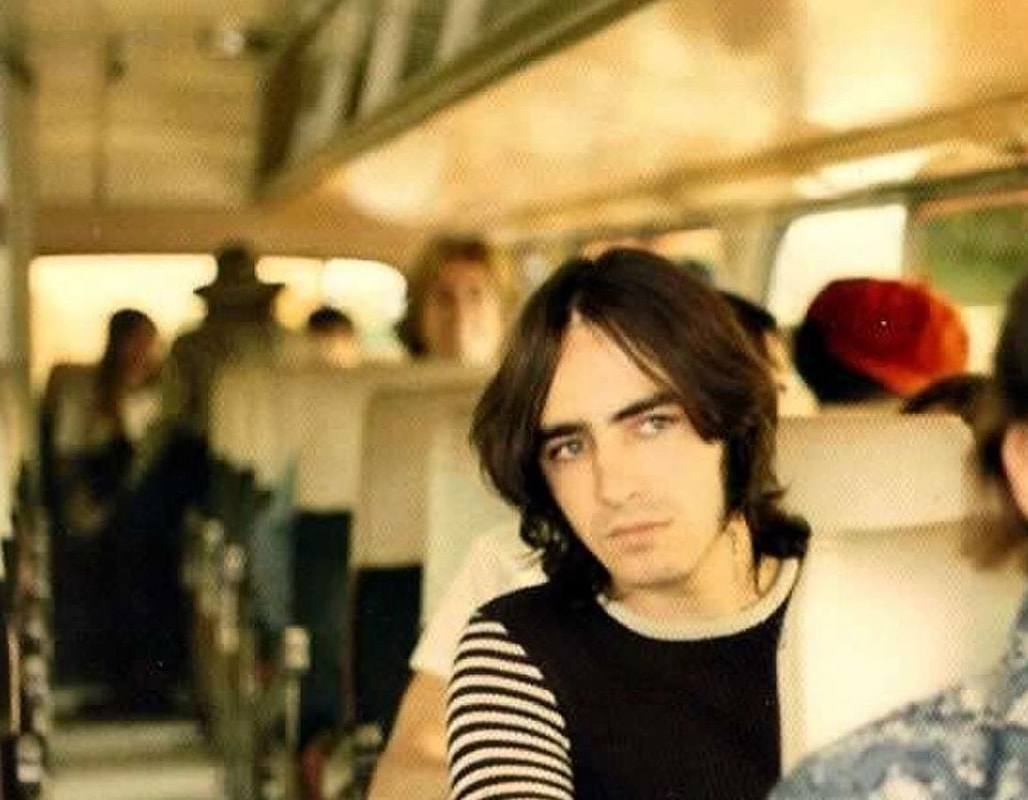

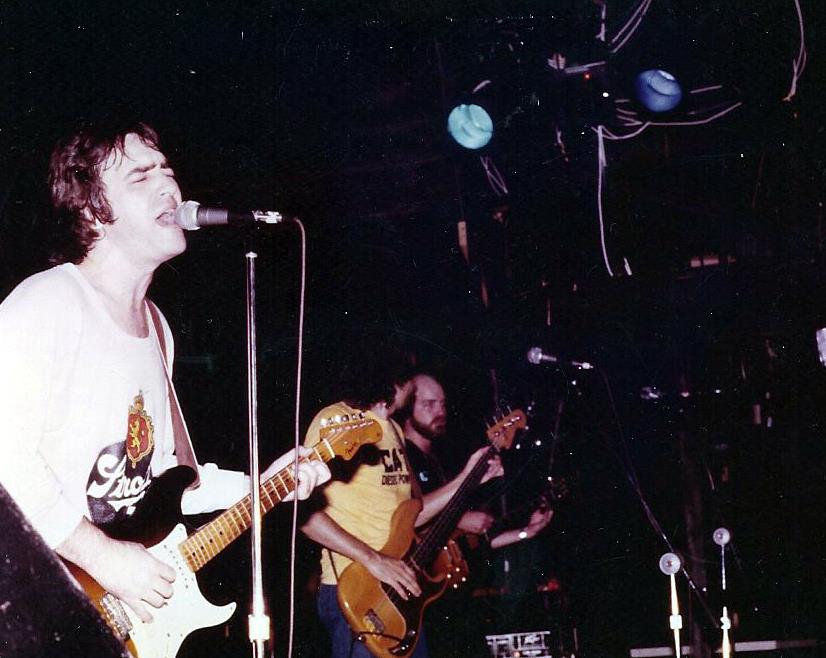

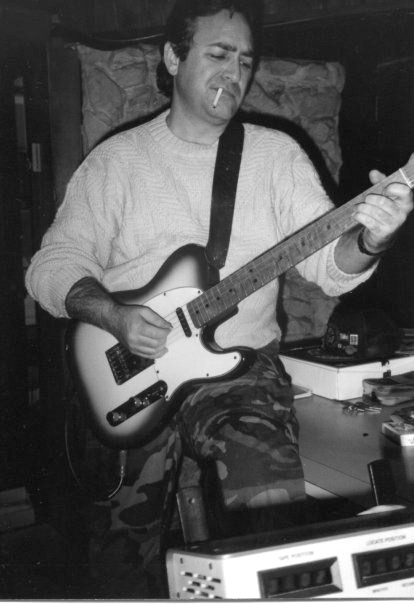

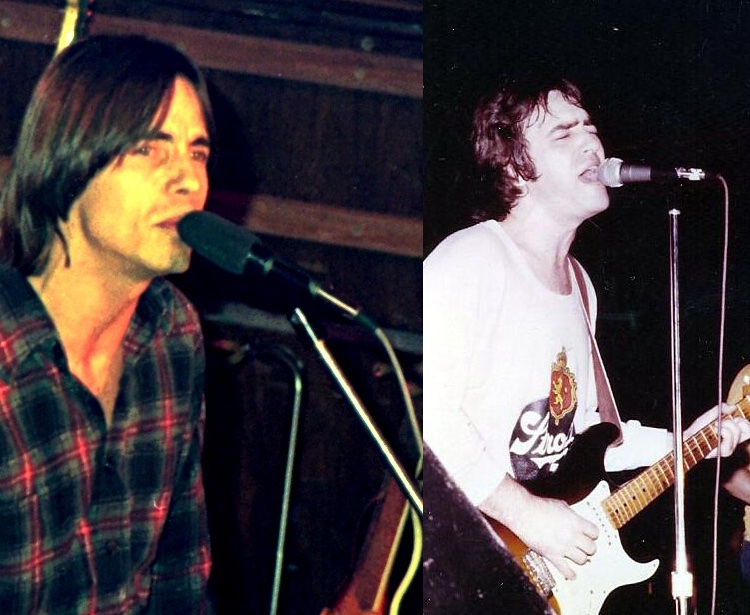

Jackson Browne playing in Germany in 1976 and Wayne Perkins playing in Birmingham around the same time in 1977 or ’78: NAJ