By Glynn Wilson –

THURMONT, Md. — Think about the picture in your head when someone mentions the word “slavery.” What comes to mind?

Maybe you think of a black man or woman picking cotton in the American South, with a huge, white columned mansion in the background. That would be a “stereotype,” as Walter Lippmann wrote about 100 years ago in his ground-breaking work in 1922 on Public Opinion, how it is formed as people are guided by “pictures in their heads.”

The second thought might be enslaved Africans engaged in agricultural operations like harvesting and processing sugar cane to sweeten the food, coffee and tea of rich white people who largely came to North America from Northern Europe and called themselves “masters.”

But can you picture the slaves employed for long hours and no pay for hot, back breaking labor in industrial operations like a pig iron furnace? The hard, dirty work involved digging the ore out of the ground, washing it and transporting it in carts to the furnace. It also involved felling whole forests of trees, burning them to make hot coals and manipulating the hot iron to make parts for Franklin era stoves, railroad tracks, iron tools and even cannon balls for George Washington’s Army of the Potomac during the American Revolution.

That is the history literally emerging from the ground here, much of it and most recently from a long lost cemetery hidden in the woods of the Catoctin Mountains, the easternmost mountain ridge of the Blue Ridge Mountains and part of the Appalachian chain that runs north from Alabama and Georgia to Maine, like the trail.

From about 1526 to 1867, historical records show that 12.5 million captured natives were shipped out of Africa as slaves, 10.7 million of them coming to the Americas. The vast majority were taken to countries in the Caribbean like Jamaica and enslaved by private British interests — even long after England officially ended slavery in 1833.

Many did make it to the South to pick cotton and keep up those masters’ plantation grounds and houses, but they also ended up in the District of Columbia building the White House and the Capitol — and in Maryland working in the pig iron industry.

The Atlantic Slave Trade was likely the most costly in human life of all known long-distance global migrations to date, historians say.

This information has been a long time in coming to light, for the officers and members of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, Cunningham Falls State Park, the National Park Service, the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History — and the scholars who are engaged in a very public debate these days about the history of race and slavery in the United States in the 1619 project and a debate about “critical race theory.”

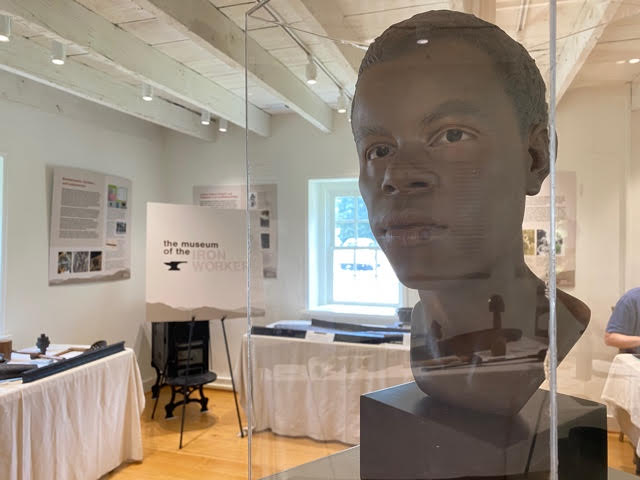

After working four decades to bring the history of this area to light, the historical society finally opened the doors of the Museum of the Ironworker last week, and the officers, members and scientists unveiled ground-breaking research at the Delaplaine Arts Center in Frederick just south of here: Facial reconstructions of two of those slaves buried in the cemetery.

There was a woman of about 35 and an infant buried on top of her, and a boy of 15.

The two busts, constructed by artists from StudioEIS in Brooklyn, New York, are on display now finally at the museum on Catoctin Furnace Road, where you can also learn about the furnace and the people, and see a collection of iron artifacts: Glynn Wilson

Archeologist Elizabeth Comer, society secretary who grew up on a farm near Catoctin — and the furnace stack known as Isabella in the valley of the Catoctin Mountains — was elected president this week. She was there at the outset of the project, suggesting that scientists at the Smithsonian should reexamine the bones found in the cemetery 40 years back by highway workers expanding U.S. Route 15, exhumed and stored by the National Museum of Natural History.

With new technology including DNA analysis and other advances in the field of forensic anthropology and genetics, scientists were able to determine the sex of the child buried above the enslaved woman and confirm that she was his mother.

“It’s easier to tell a story if you’re looking into a face,” Comer said. “We don’t know what [their] names were. And we don’t know in many cases what their jobs were. … These are people, their memory has been lost, their descendants have been lost … a legacy has been lost.”

Examining the bones of the teenage boy’s back revealed the incredible stress he labored under for much of his short life, according to Smithsonian anthropologist Kari Bruwelheide, who said researchers believe the woman suffered from Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, a painful condition when the blood supply to the ball part of the hip joint is temporarily interrupted and the bone begins to die. She likely suffered from a limp, stiffness and limited motion of her leg.

“The symptoms increase with activity, and I can’t imagine that she had one day of her life where she was allowed to stay in bed,” Bruwelheide said according to coverage in a local newspaper, The Frederick News-Post.

Yes, “Forged in Iron and Bone: Unveiling Faces of the Enslaved” and the opening of the museum took a long time to come to fruition, officers admitted when I attended their most recent meeting on Wednesday at the new museum while camping in a state park campground nearby.

The event was originally scheduled for last March, but the novel coronavirus pandemic hit the nation, so it was delayed for more than a year.

Comer and the others in the non-profit organization have patiently worked through other setbacks and delays over the years, including technical problems with the historic buildings they own and manage, including a collier’s log house, a forgeman’s house, a chapel and the iron master’s mansion.

It also took several attempts to convince Dr. Doug Owsley, the lead anthropologist at the Smithsonian, to consider a re-analysis of the remains from the lost and hidden graveyard on private property.

“These things take time, and they’re worth waiting for,” Comer said at the unveiling, which was described as an emotional night. “Here we are tonight, and it has been a wonderful, wonderful journey. And it’s not over.”

The historical society continues to work on more programs to expand public understanding of the lives of those who worked in the iron industry in the area, and the role African slaves played, with the overall goal, Comer said, of “providing an avenue for reparative heritage to facilitate social justice, economic opportunity and vindication.”

About the time of the American Revolution in the 1770s, Thomas Johnson Jr., who later became the first governor of Maryland, discovered hematite ore in the mountains here. Thomas Baker and Roger Johnson constructed the Catoctin Furnace to produce pig iron from the ore. The Catoctin forest provided the fuel to make the charcoal for the operation. Production literally began in 1776, as the founders were meeting in secret in Philadelphia northeast of here and Washington was gathering his army to fight the British.

By 1873, after the Civil War, new owners converted the furnace to coal, fueling its operation until it was finally closed down in 1903.

Comer remembers her childhood in the 1960s here, village festivals and interactions with the people who lived in the small town, who she said were all white. Records reveal that the African Americans disappeared from the area in the 1840s, but not the reason why. That’s a remaining mystery for researchers to solve.

Scientists at first were struck by the number of teenagers found in the graveyard, and wondered if the harsh furnace work played a role in their early deaths.

Experts from the Harvard laboratory of geneticist David Reich extracted DNA from the bones of 29 people exhumed from the cemetery back when it was discovered and identified five or six family groups and intriguing burial patterns.

Two baby boys were buried on either side of their mother, who was about 22 when she died.

“I called them the invisible people,” said Sharon Burnston, the retired archaeologist who directed the exhumation according to The Washington Post. “In the cultural climate of the ’80s, nobody even cared.”

In the new research, DNA helped reveal mothers and their children, and individuals who were potential siblings. Racial backgrounds were also revealed. The baby buried with his enslaved Black mother had a White father, for instance.

One research study that resulted from the find was published under the title: Restoring Identity to People and Place: Reanalysis of Human Skeletal Remains from a Cemetery at Catoctin Furnace, Maryland.

“I never thought that I would see … in my 40 years of doing this … the ability to go into a cemetery and actually through genetic means be able to identify relationships,” Smithsonian anthropologist Douglas Owsley, who helped lead the project, said at the unveiling.

Smithsonian anthropologists, who helped direct the study, found evidence of childhood diseases and congenital deformities. Craniostenosis, an abnormality of the skull, was found in an unusually high number of the dead.

The two busts, constructed by artists from StudioEIS in Brooklyn, New York, are on display now finally at the museum on Catoctin Furnace Road, where you can also learn about the furnace and the people, and see a collection of iron artifacts.

For much of her early life here, Comer said, everyone believed the village had an “unchanged European heritage” from the time of the Revolution.

“The effects of enslavement on the African-American population in the United States have been intergenerational, and reversing them will be as well,” she said. “A growing literature makes the moral, historical, legal and economic arguments for Black reparations.”

More Photos

The old fireplace in the collier’s house, sometimes used for hearth cooking demonstrations: Glynn Wilson

Very good article about a subject that is rarely mentioned.